CLICK HERE for more videos of the preparation and celebration, plus a special slideshow with more photos.

When you are Latina, life begins at 15 with the biggest party you’ve ever seen.

It is "los quince años," and to an outsider, the traditional celebration can be viewed as a mix between a Jewish bat mitzvah, an American "Sweet 16" and a debutante ball.

The tradition serves as a cultural and religious coming out party and denotes the Latina’s metamorphosis from child to woman.

Emily Ibarra, a Johnson High School student, recently let the world know that she was no longer a little girl with her los quince años. She allowed The Times to chronicle the event and the weeks of preparation leading up to it.

Although her 15th birthday was in July, Emily celebrated her los quince años on Nov. 1 in a traditional celebration complete with a church service and a party that packed the Georgia Mountains Center with hundreds of friends and relatives.

The experience involved thousands of dollars and months of planning. Emily’s mother, Veronica Ibarra, a self-proclaimed "Texican," would not have had it any other way. Since in Latino culture the groom’s family typically pays for the wedding, los quince años may be Veronica Ibarra’s sole chance to create an elaborate and unforgettable experience for her only daughter.

Mixing of cultures

The tradition of los quince años is common in Latino culture, but the way the American-born Emily and her family experienced this rite of passage was unique and involved the influences of her commingled culture.

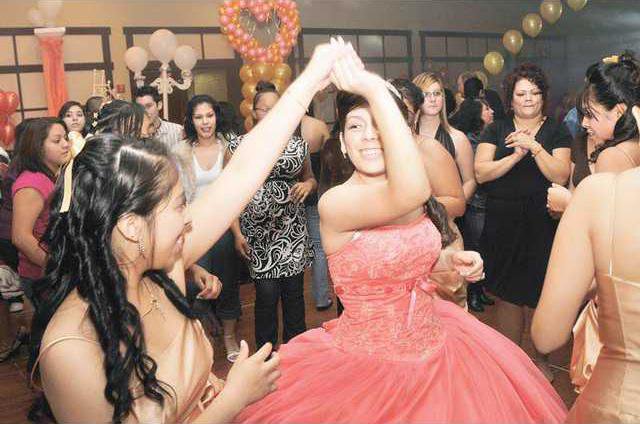

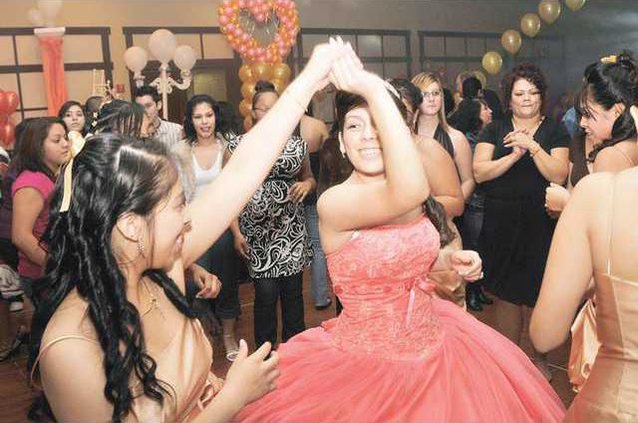

Certainly, there were the traditional choreographed Latino dances that Emily performed with her court of "los chambelanes," or male escorts, and the female counterparts, called "las damas." There were seven chambelanes and six damas who danced alongside Emily, "La Quinceañera."

In a church service, a minister prayed the traditional blessing over Emily and provided biblical guidance for Emily’s new stage of life — womanhood.

Capt. Gabriel Elias, a former pastor at the Salvation Army Church in Gainesville who now serves the church in San Antonio, Texas, illustrated the celebration of Emily’s transformation, reading from the third chapter of Ecclesiastes at the church service.

"There is a time for everything and a season for every activity under heaven," Elias read. "A time to scatter stones and a time to gather them, a time to embrace and a time to refrain, a time to search and a time to give back..."

Elias, who provides the blessing at many los quince años rituals, says the season of change that comes with the 15th birthday is one that cements the bonds of the Latino family.

"It is a time for celebration, and it is a time for the whole family and friends to rejoice and to remember that God is good to us," Elias said. The celebration is a reason for family members who live miles away from each other to come together, Elias said. Likewise, Emily’s family members traveled from Texas, Illinois and North Carolina to witness her coming-of-age.

"It keeps the family (believing) in something to celebrate, and to be united," Elias said.

Yet, the invitations to Emily’s los quince años were a sign that the Ibarras’ heritage has been altered by the surrounding lifestyle of "gringos."

Although the invitations were made in Mexico, there were two — one written in Spanish and another with a completely different aesthetic that invited Emily’s English-speaking friends to her "Sweet 15."

Even the church service that preceded the party was conducted in both English and in Spanish. Emily, a member of the universal Salvation Army Church, also did not have a traditional Catholic ceremony like many other Latina Quinceañeras, Elias said.

Emily, in an effort to make her los quince años her own, also skipped a ceremonial crowning and "changing of the shoes" in which a father figure takes flat-heeled shoes off her feet and replaces them with high-heeled shoes before La Quinceañera participates in her first dance.

Instead, Emily wore her tiara and high-heeled shoes to her ceremony.

"We don’t want to do that whole tradition thing," Emily said of a choice not to have her stepfather put high-heeled shoes on her feet before she danced for the first time at her party.

Her party, too, was infused with inescapable gringo elements. In addition to the traditional Latino dances, Emily’s celebration also included a dance choreographed to music from the rock and roll musical "Grease" and a visit from her favorite cartoon character SpongeBob SquarePants.

To Veronica and Emily Ibarra, these personal touches were the elements that separated Emily’s los quince años from all the others and made it special.

Getting ready for the event

of a lifetime

"Today, I get to be" — Emily folds her fingers as if making quotation marks in the air — "a princess. But I don’t consider myself a princess," Emily said. "Princesses are just like sidekicks."

Emily prefers to be revered as the queen for the day.

La Quinceañera is no sidekick. The preparation for her special day is evidence.

Veronica Ibarra said she began planning Emily’s los quince años in February, reserving venues and writing checks for the church service and the ensuing fiesta.

The doting mother spent months hauling Emily’s court of damas and chambelanes between their homes and hers to perfect the traditional dances they would perform when they presented Emily as a woman for the first time at the Georgia Mountains Center.

There were food arrangements to make and decorations to choose — not to mention finding the dress Emily would wear — and all of these things had to be perfect for Veronica Ibarra’s only daughter, the honor student who Veronica Ibarra said deserved the spectacular celebration of womanhood.

"I think the mother was so happy she was throwing everything through the window," Elias said.

In the months before the actual celebration, Emily’s grandmother flew to Gainesville from Texas to give her nod of approval on the dress Emily would wear for her los quince años.

Had she not approved of Emily’s choice of a full-skirted coral gown, the search would have continued, because aside from the religious rites, aesthetics prevail as one of the most important elements of los quince años celebration.

Emily missed two days of school to prepare herself for her los quince años. Had it not been for the celebration, the honor student said she would have had perfect attendance for the semester.

But Emily had to take care of the important details of how she would look on her special day — her first official day as a woman — spending the days before it having her nails and eyebrows shaped and polished to perfection.

She later spent hours sitting in a chair at a beauty salon on Atlanta Highway while her hairdresser, Camila Pantoja, separated individual strands of her black locks, inundating each one with enough hair spray to hold the shape of several tight and shiny tendrils late into the night.

Emily did not allow anything about her special day to be substandard. In purchasing her dress and her party favors, Emily only dealt with the owners of the dress shop Joyeria & Novedades Latinas. Emily made the party planners agree that the backdrops they used at her party would not be used at any other los quince años until after they had been used at hers.

"I get what I like," Emily said.

When she did not approve of the way her eyeliner had been applied on the day of her celebration, Emily scowled.

"I look gothic," she said.

Although her mother and the stylist insisted she looked beautiful, Emily was not satisfied until the eyeliner was reapplied. It had to be perfect. Los quince años only happens once.

A time to be a woman

Emily’s first dance with her stepfather at the Georgia Mountains Center was her first official act as a woman. Following that first dance, Emily’s stepfather handed her off to her main escort, the "chambelán de honor." The act was a symbol of her womanly ability to dance with men other than her father.

Before her los quince años, Emily said she had never been a fan of dancing.

"I didn’t like to dance at all — at all. You wouldn’t see me nowhere at a party," Emily said.

Her mother, however, said she saw a change in Emily’s attitude the night of celebration.

Veronica Ibarra said her daughter did not leave the dance floor until the party ended at midnight.

"She danced all night," Veronica Ibarra said. "She just danced."

With the closing of her ceremony, Emily was considered mature enough to wear makeup and wear high-heeled shoes.

There were signs after the ceremony that showed Veronica Ibarra her 15-year-old daughter was becoming an adult aside from the ceremony.

After arriving home from her celebration at 3 a.m., Veronica Ibarra said her daughter made sure to attend church the next morning.

Then, on a post-los quince años shopping trip, Emily used her birthday money to buy her mother a specially crafted ring decorated with birthstones representing Emily, her two brothers and her mother.

Emily bought the ring as a token of gratitude for her mother’s hard work. It was exactly the kind of ring Veronica Ibarra had been telling Emily she wanted for years.

When Emily gave her mother the certificate for the ring "she said ‘thank you for my Sweet 15,’" Veronica Ibarra said. "She said ‘you always talk about appreciation; I appreciate what you do.’ It meant a lot."

Now, at the age of 15, Emily Ibarra is considered a woman in the eyes of the Latino community and in the eyes of her mother. Emily, herself, says that the preparation for the party pulled her out of her shell and made her appreciate her mother more.

However, Emily says her newfound maturity likely won’t compel her to wear makeup or give up her favorite cartoon. After all, she still is only 15.

"I still watch SpongeBob."