Thanksgiving is a time when we express gratitude for the things that are important to us. We don't usually spend that time pondering the nature of existence.

But this year, it occurs to me that parents must always be at the top of your thank-you list. Even if you had a terrible relationship with your mother and father, they're the people who made it possible for you to be on this Earth.

It seems almost a fluke that I'm here at all, since my father barely made it into the world. Walter Eugene Gilbert was born in 1931 in rural western Pennsylvania. He was a surprise baby, arriving when his sister and three brothers were already teenagers.

There were no hospitals in the area. He was born in a farmhouse, and he came prematurely, weighing less than 3 pounds. By any objective measure, he shouldn't have survived. He was expected to end up in one of those tiny gravesites you see in old cemeteries, filled with infants who died at birth.

But he refused to give up. He grew and thrived, even after his own mother died while he was still a baby.

In the depths of the Great Depression, life was tough. The family managed to put food on the table only because they were able to grow it themselves on their small farm.

My dad never wanted to be anything more than a farmer. He loved animals; he loved being outdoors. But in the early 1950s, Uncle Sam came calling.

The Army taught him how to work on electronics, and then he moved into the field of computers, something most people had never even heard of. At that time, a single computer could almost fill a room.

Remember in the movie "Apollo 13," all those nerds wearing ties and short-sleeved shirts with pocket protectors? That was my dad. After he got out of the military, he worked as a civilian contractor repairing computers, and took a job with Burroughs Corp. (now Unisys).

Along the way, he fell in love with Arlene Grauberger of Cleveland, Ohio, a young woman he met in the church choir. They were married on Nov. 21, 1956.

Dad worked for a while at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base near Dayton, Ohio, where my older sister was born in 1959.

Then he was transferred to Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Ala., the rocket center that was a hub of activity at the beginning of the "space race" between the U.S. and Russia.

My parents rented a small house in Decatur, Ala., and had two more babies: me, in 1961, and my brother the following year.

Then our growing family was transferred to Memphis, Tenn. One more baby, another girl, was born in 1965. My parents seemed to be living a typical, working-class suburban life.

And then their world fell apart. Shortly after the baby's birth, my mother became paralyzed from the waist down and was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis.

Put yourself in my dad's shoes: You're 34. Your wife is 31 and will never walk again. You've got four children, ages newborn to 5 years old. You've got to keep working because you're the sole breadwinner. And you have no relatives living nearby who can help out.

What do you do? My dad just carried on as best as he could. He worked nights, and during the day he handled the cooking, shopping, picking up the kids from school. Sleep was a rare luxury.

Over a period of 20 years, my mother became completely incapacitated, and Dad was her only caregiver throughout her illness.

Now, all of that, in itself, makes him heroic. But what's astonishing to me is that somehow he still found time to be a dad.

There wasn't much money, but he made sure we all had bicycles and baseball gloves. He installed a horseshoe set in the backyard and a basketball goal in the driveway. Whenever he could, he was out there with us, playing catch and shooting hoops.

And he took us on inexpensive excursions. We went fishing. We went to the airport to watch the jets take off. While my mother was having physical therapy at the hospital downtown, he'd take us to the Mississippi River to watch the barges go by.

With limited resources, he was giving us what was most precious to him -- time.

My mother died in 1985, and a few years later Dad retired from Unisys after three decades of service. But he was bored staying at home, and soon he took a job in the computer department at Union Planters, which later became Regions Bank.

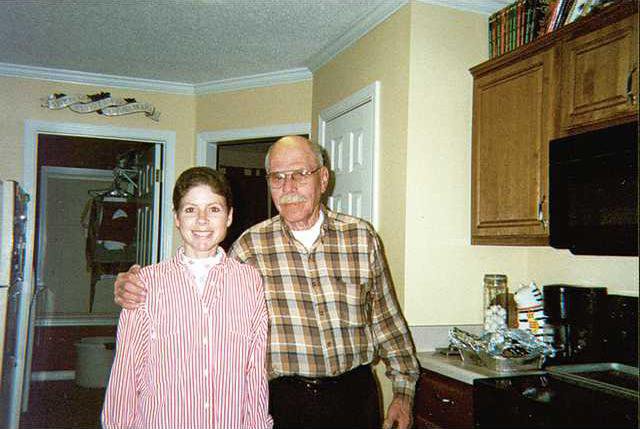

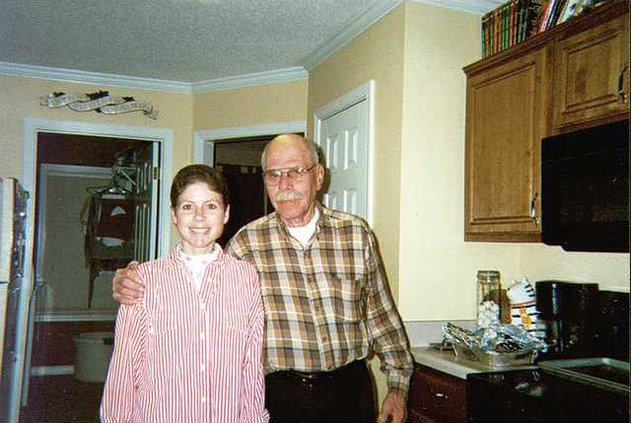

When he turned 77 this year, he was still working full-time, still living by himself in the same house we grew up in.

I think most people, if they could choose, would want to remain fully functional right up until they die, rather than lingering for years with a progressively debilitating disease. After seeing what my mother went through, I am sure this was what Dad wanted for himself.

And that's how it happened. On the last weekend in September, my father suffered a cerebral hemorrhage. No one knew anything was wrong until he didn't show up for work on Monday. My brother and sister went over to his house and found him unconscious, lying in a pool of blood.

What's amazing is that he was still alive. A doctor later said that he had probably been there for at least a day before he was discovered. The tenacity and strength that had carried Dad through infancy were still with him at the end of his life.

But his will to live could not overcome a traumatic brain injury. As soon as doctors determined that there was no hope of Dad ever regaining consciousness, my siblings and I agreed to take him off life support. He died early in the morning on Oct. 1.

I wrote the eulogy for Dad's funeral. It was basically a list of things I wanted to thank him for, things that helped shape me into the person I am today. I talked about what we had in common: a deep appreciation for classical music, a fascination with vintage aircraft, a weird sense of humor.

But of all the things Dad and I shared, probably the most influential was an affinity for dogs. I've never seen anybody who loved dogs the way my father did. If he saw a stray dog on the street, he felt compelled to coax it over so he could pet it.

Unfortunately, my mother hated dogs and was adamantly opposed to having one in our house. But when I was 7, my dad overruled her. He took us out to "Culp's Hound Farm," and we picked out a 3-month-old basset hound we named Butterscotch.

Before long, my mother banished the dog to the backyard. But I was the main person who fed and walked him, and that led me to a lifetime of training and caring for dogs. When Butterscotch's health failed 10 years later, my dad and I both held him as he was quietly put to sleep.

Among dog folks, there is a legend about the "Rainbow Bridge." This is the belief in a place where all of the dogs you've ever owned are waiting for you, and when you die, they cross over the bridge to meet you.

I don't really believe there is such a place. But wouldn't it be cool if there were? I think if Dad ended up surrounded by all the dogs he ever loved, that would truly be his idea of heaven.

Debbie Gilbert is a Times reporter.