Faye Bush knows the Newtown Florist Club is more than flowers and environmental justice — it's about taking care of the community.

The club celebrates its 60th anniversary this weekend. Bush, executive director of the group, has seen Newtown, her neighbors and the city's needs change in the 58 years since she joined the group at age 18.

"It means a lot to think about how we started and the things we ran up against," Bush said Wednesday. "We didn't know what we were doing at the beginning with the environment, but we knew grain dust came out and covered the kids, and you couldn't sit on your porch."

The homes were built atop an old landfill east of Athens Street in the years immediately after the 1936 tornado to serve as the "New Town" for black families displaced by the disaster. Industries such as Purina and Cargill didn't move in until the 1950s and 1960s.

Bush's mother, Maggie Johnson, was one of 11 women who founded the club in 1950. The women traveled door-to-door in the neighborhood for donations to purchase flowers for Newtown residents' funerals.

They would dress in white during the summer and in black during the winter, carrying funeral wreaths to the churches and to the cemeteries.

"It was a scary time back then. I ran a little store and there were slum houses nearby without toilets," she said. "When we started to take a stand, people started calling me and threatening me. It hasn't been a pleasant ride for those 60 years."

As the club gathered flower donations for more than 20 years, the women noticed an alarming number of deaths in the community. Bush noted a trend in health problems, and in 1978, the florist club asked the state Environmental Protection Division to force Purina to address sewage odors and the blanketing grain dust.

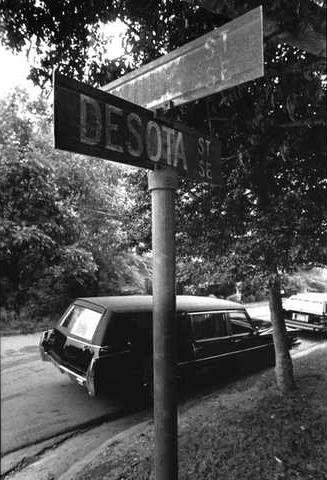

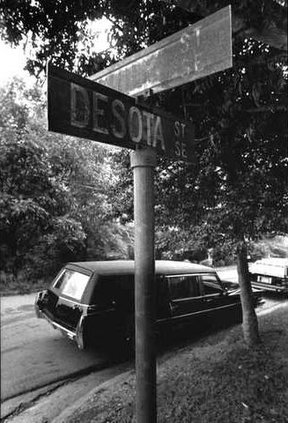

In 1990, the club sponsored a survey of Desota Street residents, which showed similar types of cancers and respiratory problems. The study was unscientific, but later that year, the state Department of Human Resources confirmed a higher rate of throat and mouth cancers in the neighborhood. The state office of epidemiology later attributed the high rate to a lifestyle of smoking and drinking.

Throughout the years, the group has complained about surrounding industries and noise pollution, but Bush said she feels like she's seen little progress.

"Several people, like lawyers, come in and think they can get the junkyard moved and then they vanish away," she said. "I guess it was hard for them to come up against the system."

Blaze junkyard workers met with Bush and other Newtown members about a month ago, but Bush still isn't satisfied.

"It's amazing they finally let us go over, but we couldn't go into their storage building," she said. "You could also tell they had just put down gravel and made it nice. It was so clean you could eat off the ground."

Throughout the years, the club has started communitywide efforts to improve Newtown, including a leadership program for girls to teach them self-esteem. The six-week program still runs each summer.

"We're getting on in age, so if we don't teach them now ..." Bush said with a laugh. "We want them to be able to carry the struggle on, and I'm always impressed with the summer program. The girls are so excited and ask amazing questions. If one of them makes something happen here, it will be well worth it."

In 2000, the group fought for a portion of Myrtle Street to be named Martin Luther King Jr. Drive.

"All the little cities around here have an MLK street, so we decided that we would get signatures and see how many would want to rename it, and our girls leadership group went around and got 1,000 signatures," Bush said. "I didn't know we would run up against so much then. We had to go before zoning and planning and then the city and then zoning again and then the city again."

Now at the 60-year mark, the club is looking for a way to keep moving forward. The ultimate goal is green space, no junkyard and a welcoming sign into Newtown.

"If the junkyard was gone, the dream is to have a walking trail that could connect us down to Midtown and eventually the mall area," Bush said. "We're trying to get the houses brought up to standard and have green spaces and places for the kids to play."

In July, Cargill donated $20,000 to create a community garden named in honor of Ruby Wilkins, the first Newtown Florist Club president. Bush came in as executive director in 1990.

"Miss Ruby Wilkins was my hero. She and I used to work so hard and go to city meetings. When she was on her deathbed, she told me to not give up and keep fighting," she said. "When I want to give up, those voices come back to me.

"Now I'm deciding who's the next person to train. Everything is getting so technical, and I don't have those skills, though I will always be a part of the Newtown Florist Club."

On Wednesday, Annette Westbrooks, the club's treasurer, and Delinda Luster, co-chairwoman of the community's beautification committee, worked at the Desota Street house in preparation for the three-day environmental justice conference the club hosted this weekend.

"I'm proud of the dedication and working so hard and trying to improve the community and get people involved," said Westbrooks, who has been part of the club for 15 years. "I'm proud of trying to get the factories around here to stop putting out so much pollution, and I'm proud to see Ms. Bush get some awards. There are a lot of things we've done over the years. We are doing some things that are really right."

The most recent project, headed up by Luster, is the revitalization of the Newtown area with the community garden and neighborhood cleanup.

"I've always lived over here except 10 years of my life, but I never took the time to join as they made a lot of differences with pollution and things like that," said Luster, who joined the club about a year ago. "Now we're cleaning up the community and trying to get it to where it will be such that anybody would be proud to live over here."

As the fight keeps going, the women know how to stick to their roots. They still carry out the original purpose of the organization.

"When we first started out, we used to go as far as help bathe sick people and go to the store for them. We even buried a man when the family didn't have enough money," Bush said. "We can't do funerals as much anymore, but we still take flowers sometimes when a family wants us to be there, and we still wear our white in the summer and black in the winter."