Though the poverty rate remained about the same across the nation and in Georgia between 2013 and 2014, Hall County experienced a healthy decline, according to the latest census figures released Thursday.

Last year, about 16.6 percent of Hall residents still lived below the poverty line, which is about $24,000 or less in annual income for a family of four. But that’s down from 21.9 percent in 2013.

Connie Parker recently moved back to Hall County from Alabama with her adopted grandchildren. She lives on a fixed income and has not yet begun receiving food stamps to help support her family.

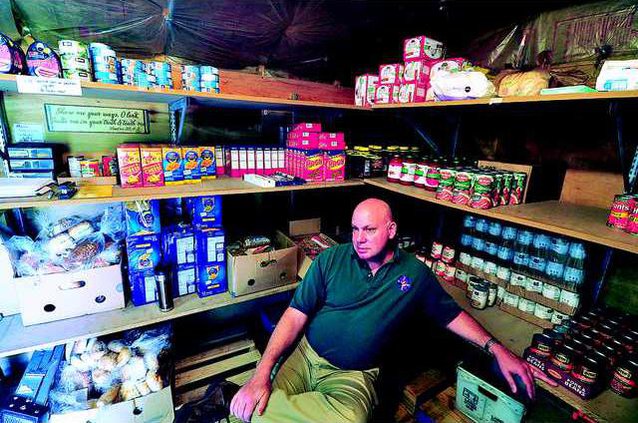

Parker was at the South Hall Community Food Pantry in Oakwood on Thursday morning to pick up canned goods, cake and some staples for her grandkids.

“They are awesome,” she said of the food pantry. “It’s kind of amazing. The food is really good.”

Nearly 7,500 of about 63,000 households in Hall received food stamps in 2014, according to census figures.

About 45 percent of those households receiving food assistance locally live in poverty.

The majority are white, accounting for 52.6 percent of all food stamp recipients in Hall, followed by Latinos at 23.9 percent and African-Americans at 20.4 percent.

The median income in Hall is $52,519, but only $23,401 for food stamp recipients.

The food pantry has been particularly busy this summer, according to Barbara Todd, who has been volunteering there for years.

More and more seniors are looking for food, and others, like Parker, are currently without food stamps.

“I think that’s been quite a few of them,” said Andrew Seibert, pastor of the Christ Lutheran Church in Oakwood, adding that all racial demographics are hurting.

In Georgia, 18.3 percent of residents lived below the poverty line last year.

And nationally, the poverty rate fell to 14.8 percent, with decreases seen across racial demographics.

Job growth, new development and slight increases in wages have helped lower the poverty rate across the nation, but millions of Americans remain on the financial ropes.

Like the federal unemployment rate, which excludes some individuals who have been out of work for long periods of time, the official poverty rate might not reflect the full extent of who is poor.

The census also includes a “supplemental poverty measure” as an additional indicator of economic well-being.

This rate accounts for foster children, tax credits, housing assistance and benefits like food stamps, while the official rate only includes pre-tax income. It also deducts for expenses on critical goods and services.

For example, not including the earned income tax credit and child tax credit, the supplemental poverty rate would have been 18.4 percent rather than 15.3 percent.

The supplemental poverty measure also reflects the growing number of elderly Americans, many of whom live on fixed incomes supported by Social Security or disability checks, as well as those who cannot find full-time work or live on minimum wage.

And that’s where people like Wendy Glasbrenner step in to fill a need.

She is managing attorney with the Gainesville office of the Georgia Legal Services Program, which works to decrease poverty levels and provides free services to eligible low-income residents.

They represent clients eligible for food stamps, Medicaid, Temporary Assistance to Needy Families unemployment compensation and subsidized housing.

“The loss or wrongful denial of any of these benefits sends families into a dangerous spiral,” she said.