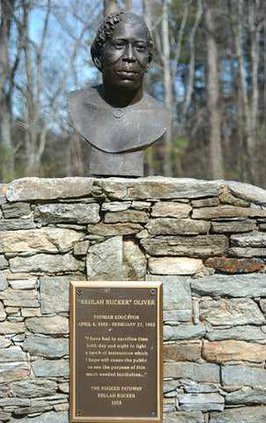

Beulah Rucker Museum and Educational Foundation

Where: 2101 Athens Highway, Gainesville

Visitations: By appointment; call 404-401-6589

More info: rojene@bellsouth.net

Standing out against the brown hill and wintry gray trees off the highway, a 100-year-old square dwelling, painted bright red with a shiny tin roof, quickly catches the eye.

Inside, the desks are empty and piano has not been played in some time. More than 50 years have passed since Beulah Rucker Oliver's Industrial School closed. Yet her spirit lives on through a foundation that shares her passion for education.

Rojene Bailey is Oliver's grandson and serves as the executive director of the Beulah Rucker Museum and Educational Foundation.

"This (school) pretty much tells the history of African-Americans in Hall County," Bailey said.

Oliver's path to opening the Industrial School wasn't just difficult; it was nonexistent. But she wouldn't take "no" for an answer.

"She was just an intent woman," Bailey said. "She wanted to educate people and that's what she did."

In her biography, Oliver, who was born in 1888, said that she wanted to be a teacher from her first day at school. Her parents tried but ultimately could not afford her education, room and board. She milked cows and began performing housecleaning duties for the principal's wife so she could continue her studies.

Upon graduation she had two choices: continue on to college, or follow her heart and establish a school. She didn't have money for either.

After working as a teacher and performing odd jobs for a few years she searched for a site for her school. Though she had never been there, a vision told her that the school would be located in Gainesville.

After initially opening up closer to town, Oliver eventually bought a few acres in the country where the students could raise their own food and the school had room to expand. This is where the museum stands today, just south of Gainesville off U.S. 129 between Athens Street and Lenox Drive.

Oliver's institution was more than just a school, it was a life. Many students lived on site, sleeping on classroom floors until dormitories were built later.

The students learned carpentry, sewing, block-making, and "all kinds of industrial arts," Bailey said. But they also studied religion, geography, history and science. They took physical education classes and participated in plays and spelling bees.

At its peak the Industrial School enrolled 200 students at one time, and they all referred to its founder as "Godmother."

"They always had kids here; they never lived alone or as a family." Bailey said.

Today the best-preserved remains of the school include a 100-year-old square building that functioned as both a residence and classroom until the 1950s.

A museum now, visitors can view a few artifacts from the school and follow a timeline of African-American educational institutions, seeing the development of the Industrial School through black and white photographs.

It is not uncommon for Bailey's friends and others visiting the museum to recognize their relatives in the old photographs. One friend identified his father as the focal point of a photo taken within the old block workshop. His father and the other young men are sitting at sewing machines, their fedoras hung on the wall behind.

"Guys did sewing then," Bailey said. "It was not a problem."

In the hall of the little residence, Bailey pointed to a formal photo of four women, each wearing a white cap and gown.

"That's my mother," he said, pointing to the woman at the top right corner of the photo. "She was beautiful."

Bailey's mother and aunt revived the memory of the Industrial School in the early 1990s by creating a foundation. They restored the little square building and made into a museum.

"They did an excellent job of getting this place up and going," Bailey said.

Bailey and his cousin continue working to preserve the site and its history, and carry on Oliver's vision.

"We're focusing on the 21st century and the education of the youth," Bailey said.

The Beulah Rucker Museum and Educational Foundation sponsors programs that encourage kids to stay in school, such as Generation Inspiration. Its yearly Back to School Rally provides children with school supplies at a fun event.

"We just want to get a good positive message out about the importance of staying in school," Bailey said.

While a multiuse educational facility has been built on site and painted the same color as the museum, ultimately the foundation hopes to build a recreation center with a gym. They want a place for children to go after school.

"We are all working hard, trying to make this place a viable part of his community," Bailey said.

If she were alive today, Bailey said, she'd be teaching computer programming and other new technology.

"She believed in keeping up with the times," he said.