Memorial Day parade

When: 10 a.m. Monday

Where: Green Street from First Baptist Church to E.E. Butler Parkway, Gainesville

How much: Free

More info: Dave Dellinger, 770-718-7676, or Roger Keebaugh, 770-869-7941

Coming Monday

- Read about Mack Abbot who is a Pearl Harbor survivor and grand marshal of the Memorial Day parade.

- Van Peeples shares about the history of the World War II monument in New Holland.

- Find more information about the Memorial Day parade and associated road closings.

Through their early years, the boys’ world seemed bounded by small-town and rural living in North Georgia.

The Woodrings family moved to Gainesville from Blairsville seeking greater opportunities, but nothing would change life more than World War II breaking out and Uncle Sam’s call to arms.

Arnold, Loy and Vaughn Woodring responded, and their service carried them across the globe and into the middle of major historic events.

“It was quite a trip for a young man who hadn’t been anywhere,” Vaughn Woodring said.

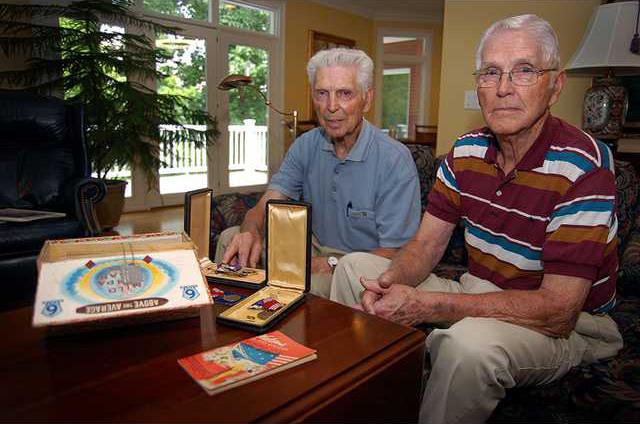

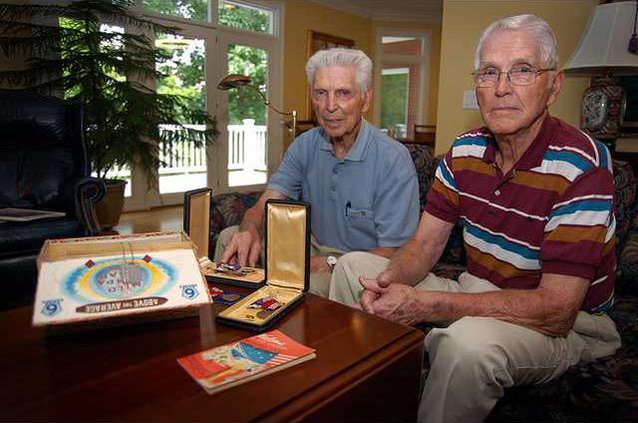

Loy and Vaughn, both Hall County residents, and Arnold, who lives in Smyrna, recalled their wartime experiences in interviews this month by phone and at the South Hall home of Loy Woodring’s daughter, Debbie Brewer.

Their stories included memories of seeing U.S. Gen. George S. Patton yelling “If they can’t get me, they can’t get you!” to U.S. invasion troops, getting pinned down in a French field by enemy gunfire and helping carry Marines to the blood-stained Japanese island of Okinawa.

Arnold’s story

Arnold Woodring, 91, was on the front lines of battle for a year, going first to Africa and later invading Sicily. He recalled arriving in northern Sicily and Germans starting to cross over to Italy in boats.

“We decided to stop them from going over there because we knew we would have to fight them later,” he said. “We then regrouped and went to southern Italy, invading there.”

An even greater struggle was about to begin for Arnold.

Army infantry invaded Anzio Beach, about 25 miles out of Rome, in an effort to draw German troops out of France and dilute Nazi opposition to the impending Allied invasion at Normandy.

“We didn’t do very well there. Our information was there wouldn’t be many Germans there, and we ended up facing nine divisions,” Arnold said. “We were outnumbered. Everybody in my outfit was either killed or captured.”

And soon Arnold’s outfit was surrounded by German forces.

“We didn’t have food or any more ammunition and our guns were about burned up, so we sat there for a day or two,” he said.

Eventually, Germany’s elite SS troops arrived with a “bunch of tanks” and rounded up American soldiers, taking them to Rome. The soldiers then were placed on a train headed to Germany crossing through the Brenner Pass between Italy and Austria.

Arnold was a prisoner of war for 14 months.

Living mainly on bread and the occasional bowl of barley, “some of us starved to death,” he said. “The only thing on my mind was food. I would dream about it at night — I was just hungry all the time.”

During an air raid, Arnold and other POWs were taken to a bomb shelter.

“I saw Hitler as he was leaving town,” he said. “He and his staff were in three cars. ... He was in the back seat by himself, and everybody was hollering at him.”

Arnold saw two other famous U.S. figures. Gen. Dwight Eisenhower and his staff brought him and other soldiers some cigarettes while he was in Paris waiting for a ship.

“And I saw Patton a lot on the front lines. He was really reckless and got chewed out a lot,” Arnold said. “But what I liked about him is he wouldn’t send you where he wouldn’t go himself.”

Eventually, Arnold was able to escape to the American side during a battle with the Germans. At the time, he and other POWs had been in fields picking potatoes.

Loy’s story

Loy Woodring, 88, was working at the New Holland mill in a government job making 32 cents per hour.

He was able to get one deferment from the war and was offered another one, but he turned it down.

Loy remembers thinking at the time, “I’m no better than the other guys. They don’t want to go any more than I do.”

After 16 weeks of basic training in South Carolina, he went to Europe in June 1944, after the Allied invasion of France on D-Day.

The Army soldier started fighting at Brest, France.

“One Sunday morning, we went into position near some hedgerows. Our orders were to go across a field overlooking a valley,” Loy said. “When we did, everything broke loose.

“We began (the battle) with full strength, with about 42 in my unit. By that evening, there were 11 who were not wounded or killed and I was the only one in my squad that was not wounded or killed.”

At one point, he lay on the ground and began reloading his rifle when shrapnel nearly knocked the weapon from his hand.

“Basically, they could see every move we made, but we didn’t see a German all day long,” Loy said. “When I pulled my arm around to get circulation, they started machine-gun shooting at me.”

He drew as close as he could to the ground, then noticed a soldier crawling toward him and crying for water.

“I told him I’ve got water, but if I move, they’ll shoot me,” Loy said.

A medic ran in and dragged the soldier behind a bank into a roadway. By crawling backward, Loy was finally able to get out of enemy sights.

Loy fought up to before the Battle of the Bulge, the last German offensive on the western front. He was wounded in Germany, just before crossing the Rhine River.

“A rifle bullet went in and out of my steel helmet ... and just made a big gully in the side of my head,” he said.

He saw no further action, ending up in a hospital in Paris, and returned to the U.S. in January 1946.

“I have one big regret till today. I was the only person I heard pray (that Sunday in France), and I was not a Christian at the time,” he said. “I might have been able to help somebody else who might not have been prepared for the next life.”

Vaughn’s story

Vaughn, 85, went into the Navy in July 1943, completing boot camp in San Diego, then going to gunnery school for several weeks.

He then headed to Pearl Harbor and joined the crew of a landing ship.

From there, with a load of equipment and Marines, Vaughn’s ship took part in an invasion of Saipan in the western Pacific. The Navy ship headed to Guadalcanal, picked up more Marines and equipment for another invasion west of Saipan.

“I’ve got respect for the Marines — they really carried the ball. They had a rough war to fight and really paid the (price),” he said.

Vaughn also took part in missions in the Philippines and Okinawa, Japan, before coming home on his first leave.

“I was home when they dropped the (atomic) bomb (on Japan),” he said. “My brother and I were coming back from North Carolina when we heard about it. That bomb killed a lot of people, but it saved a lot of American and Japanese lives.”

At the time, the Americans were planning a mainland invasion of Japan.

For all his military ventures across the South Pacific, “mine were an easy trip compared to his,” Vaughn said, gesturing toward Loy.

One rough spot for Vaughn during the war was learning about Arnold.

“My gunnery officer called me to his quarters one night, said the USO had sent a letter saying Arnold was missing in action,” he said. “It was quite some time before I got word he (had been) captured.”

Loy, nodding his head, recalled hearing the news, as well. “It was really devastating,” he said.

Life after the war

Eventually, the brothers were reunited on U.S. soil, as their military careers ended.

But jobs at home took them in other directions.

Vaughn ended up working for National Life and Accident Insurance Co. for 31 years, retiring in 1980. Loy returned to New Holland Mill but went on to General Motors, retiring from there in 1985. Arnold worked for Sears for 40 years before retiring.

The brothers have other family ties to the military, including a younger brother, Evan, who served in the Air Force after World War II, and a brother-in-law who was wounded in Germany during the war.

They also had an older brother, L.B., who was married at the time of the war and didn’t join the service. They also had three sisters.

“We were close growing up,” Vaughn said.

Of the siblings, two sisters and the oldest brother are dead.

Memories of the war still linger and some of them are painful.

“At times, I have depression about it,” Loy said. “For a long time, I wouldn’t talk about it without high emotions.”

The three men recently took an all-expenses-paid trip to the World War II memorial in Washington, D.C., as sponsored by Honor Flight Network, an Ohio-based nonprofit organization.

“It was marvelous,” Loy said of the experience. “Everybody was good to us. They fed us and treated us well.”

He added with a grin, “Everybody was treated like royalty, but us together — the three brothers — we got a few more pictures made, probably.”