Joan Praet winced somewhat as she heard the word.

“Closure is such a strange word, isn’t it?” she said.

Forty-one years after hearing the devastating news that her first-born son, Gary, was declared missing in action, the South Hall County woman learned that his Air Force identification tags had been discovered at a military excavation site in Laos.

Officially, his status changed in 1975 to killed in action based on a “thorough review of the circumstances.” Praet had long suspected her son’s C-130 Hercules had crashed in some enemy-ridden jungle.

But there was never a body discovered, no flag-draped casket shipped home — and no certainty of knowing what happened to Senior Master Sgt. Gary Pate on May 22, 1968.

That is, until Praet received a phone call from the Air Force on May 26 this year. Excavation at the crash site revealed no remains but several personal items, including her son’s dog tags.

“I was glad I was here by myself when I got the call,” said the 84-year-old mother of four, who has lived with her son, David, for 12 years. “... I just sort of went to pieces. I got it together, and then David came home from work, and I told him.”

The revelation may close a chapter for Pate’s family, perhaps confirming suspicions of his fate. But the anguish is still there, even ripping open old wounds.

That’s especially true as the family prepares for an Oct. 3 memorial service in Fayette County and a yet-to-be scheduled military ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

“It still leaves a hole in your heart,” Praet said. “... It just is and stays is and doesn’t go away.

“What I have found that’s been difficult, if that’s the word, is when you meet people for the first time and they say, ‘How many children do you have?’” she said. “There’s no way I can make myself say, ‘I have three.’”

Early life lessons

Gary Pate’s story begins long before he stepped aboard the C-130 with seven other crew members, headed for their last mission from their base in Okinawa, Japan.

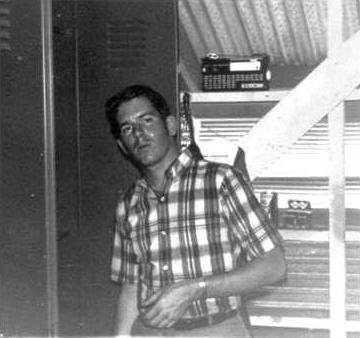

He was born in June 1946 in Atlanta to Joan and Loyd Pate. His mother was a Hyde Park, N.Y., native, who had lived in Georgia since 1945. His father was Newnan-born Loyd Pate, who painted automobiles.

The Pates had three other children — Elaine, Kenny and David, from oldest to youngest, all born in Atlanta.

The family moved to Hiram in Paulding County and then to Starr’s Mill in Fayette County in 1958.

“Gary was 12 and we lived there until I moved in 1980,” Praet said. “The kids all went to school in Fayetteville.”

He graduated from high school in 1964, where he was active in the Future Farmers of America. He also took part in Boy Scouts and church activities.

Gary then went to work in the X-ray department at South Fulton Hospital in East Point, where his mother was an office manager.

“It was fun. We carpooled — Gary rode with a bunch of women,” Praet said, smiling.

She recalled one somber occasion when her son stepped into her office, tears on his face. A man he had taken in for X-rays had just died.

“It was really difficult for him to grasp the suddenness of here today, gone tomorrow,” Praet said.

Praet and her husband had no clue their son was interested in the Air Force until one evening, about a year after he graduated, when he announced to his parents that he had enlisted.

Letters home ‘always cheerful’

Going from home to the military required some adjustment for Gary, who suffered from homesickness, his mother recalled, noting the frequent, yet eagerly accepted, phone calls.

“He came home every opportunity he had,” she said.

While stationed in Tennessee, he met a girl, Becky, and they became engaged. “She came to see us quite a bit. I liked her fine,” Praet said.

Gary traveled to several places, including Germany, Hawaii, California and Wyoming.

“He took advantage of every opportunity to travel, and ended up in Okinawa,” Praet said. “His letters were always cheerful. I was never truly concerned.

“There was one lady in particular (at South Fulton Hospital) whose husband was a pastor ... and she would always say to me, ‘How’s Gary?’ and I would say, ‘Fine — there’s no other way for him to be.’

“It never occurred to me there was any danger. His letters never (implied it). I did not know he had signed up for this night flying. It was supposed to cut six months off his stay.”

Gary was a load master aboard the C-130, which served as “flare ships” that lit up the skies of the Ho Chi Minh trail in Laos and southern North Vietnam.

Even in the midst of war, he was busily preparing for his future.

“I still have his cummerbund from his having gotten his wedding suit made in Japan,” Praet said. “He had ordered china ... and all things were go.”

She also recalled her son’s love of country music, having seen iconic figures Patsy Cline and Boots Randolph in concert.

“He loved photography. Later, they would say he was never without his camera, but there was not a camera in his things that they sent home,” Praet said.

Bad news comes suddenly

“I was totally unprepared for the Wednesday night when these two young airmen knocked on the door at about seven o’clock,” Praet said.

They delivered the terrible news.

“He was on one of two planes that had flown the night mission with no ammunition, just magnesium flares that they were dropping over the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

“Their mission had been accomplished and they were on their way back, and they lost radio contact with the other plane, which went on to Okinawa, (where) they waited a bit and realized (Pate’s plane) wasn’t going to come back.”

The plane flew back to where they had lost communications.

“There was a fire on the ground but too much enemy action to get close enough to tell whether or not there was a plane down.”

The airmen “stayed with us several hours that night,” Praet recalled. “... They wouldn’t leave until the pastor from the church came.”

She said she has since wondered how initial reaction to such news must vary from family to family.

“I was in total denial. I told them they had the wrong house,” Praet said.

Her children were at home at the time.

“It was very traumatic,” Kenny Pate recalled. “I didn’t know what was going on. Nothing was sinking in — it was like a dream. I remember my dad and my mother and their reactions, and their reactions influenced our reactions.

“It was a night I’ll never forget. It happens all the time, I know, but I don’t wish it on anybody to have to go through that.”

David said he never expected such a tragedy involving Gary, whom he considered his hero.

“The mystery of not knowing (what happened to him) is what has been hardest on me and I’m sure (that’s the case with) everybody else here,” he said, surrounded by siblings, their spouses and his mother.

“My fear was that he had been captured and tortured all this time,” he said. “I think I would have been better off finding out that they had found his remains.”

Elaine Pate Griffin said, wiping away tears, “I kept expecting him to come home. That was all I wanted.”

Kenny said, “The thing that sticks with me — that makes me feel good about this — is that he joined (the Air Force). He was not drafted. He was doing what he loved to do. ... The way to go out (of life) is loving what you’re doing — that’s what I carry with me.”

Presidential comfort

After that dreadful night, someone with the Air Force visited Praet periodically at the hospital “and bring pictures of prisoners of war, blindfolded or whatever shape they might be in, for me to look at,” she said.

“That went on for quite a long time.”

She later met the wives of the C-130 pilot and co-pilot.

“I didn’t learn a lot, but it was comforting and interesting to meet people (in similar situations),” Praet said.

She also went to Washington, D.C. in the early 1970s to look at records and take part in meetings “to tell us what to expect in the event our prisoners came home.”

Through the years, Praet received Christmas cards from all the presidents through Bill Clinton — except Jimmy Carter — wishing her the best during the holidays, given her son’s absence.

Initially, she received a letter from President Richard Nixon on April 19, 1973, that read, in part, “You have endured a long and trying vigil. I know how difficult it will be for you and your family to further bear the anguish of this uncertainty.”

Praet has framed the letters and cards, hanging them on the wall of the stairwell that leads to her living quarters in David’s home.

Praet’s husband, who suffered from heart problems, died in 1970. She remarried John Praet in 1981, and he died in 1988 of pancreatic cancer.

Gary’s fiancee kept in touch with Praet for about a year after the tragedy. Praet said she later heard that she got married.

Status changed

In 1975, the military informed Praet that her son’s status had been changed to killed in action.

“There has been no information from any source, including debriefing of returned prisoners, which would indicate his survival,” the letter said.

In 2002, she learned of Air Force plans to excavate crash sites from the Vietnam War era.

“They had to get permission to go into these countries ... and they were not too cooperative to begin with,” Praet said. “And they began several years ago to let them go in.”

Over the years, coping at times was difficult, but “you just keep putting one foot in front of the other and one day at a time,” she said.

“Just like Elaine never gave up thinking he would come home, I think I accepted (he wouldn’t) several years afterward.”

At one point, Praet met the wife of one of the crew members who had ended up living in Albany.

“I went there to spend the weekend with her and she told me very frankly that there had been an explosion, that the plane had been hit by a (surface-to-air) missile and it’s impossible that anyone was saved,” she said.

“I had hoped that it was an instantaneous (death for Gary) — here today, gone tomorrow, wake up in the arms of Jesus,” Praet said.

Planning a final goodbye

And now the family is preparing for Saturday’s service at New Hope Baptist Church’s south campus.

The program still needs work, but plans so far include a slide show and an honor guard. Griffin said Gary’s three best friends from high school said they plan to attend.

The service “is going to be difficult,” said Griffin.

David Pate agreed.

“This thing that we thought we had already settled is being dredged up again, and it’s hard,” he said. “It’s just tough to pick this up again.”

“I’m not sure it’s stuff that will ever go away,” his sister said.

Kenny said asking time off from work to attend the service has been tricky. The human resources director at his job “had to talk to her superiors to make sure it was clear for me to have time off when I needed it.”

“There’s no body, there’s nothing to say Kenny Pate’s brother died and his funeral with be ... there’s a lot of blank,” he said.

“But anybody who will sit and listen to me, I will tell them the story — and I’m proud to. It’s a good story. It’s sad, but I’m putting a good period on the end of it.”

David Pate said he also is proud his brother is “finally getting the recognition, after all this time, that he loved and served this country.”

“For all the things this country does wrong, that’s one thing we have done right. I’ll stand on top of any building and say (the Air Force) kept after it ... until they found out (Gary’s fate).

“They didn’t give up, and that’s what makes me feel very, very proud to be an American.”