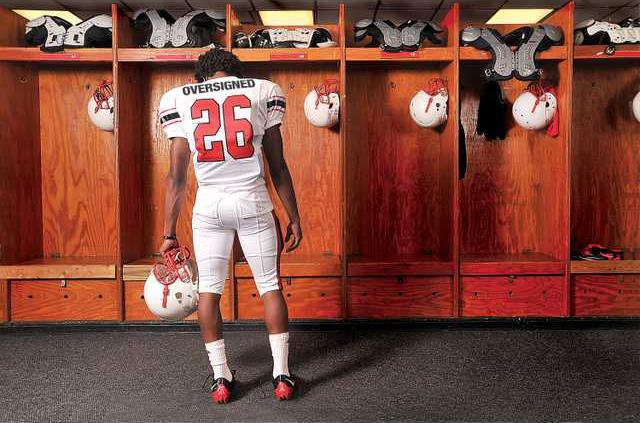

Roster management.

The phrase sounds harmless enough. But when applied to college football programs, its implications can be devastating and life-altering for a student-athlete.

Football Bowl Subdivision programs are limited to 25 initial scholarships per season, and cannot not exceed a total of 85 scholarships at any given time. However, a one-sentence bylaw doesn’t begin to cover all the aspects that go into the game of college football recruiting.

Every year, numerous big-time programs sign well over the 25 allotted scholarships to help form a roster. In 2009, Ole Miss signed 37 student-athletes to football scholarships. Last year, Auburn led the country with 32 signees. Since Nick Saban arrived at Alabama in 2007, only once have the Crimson Tide signed just 25 student-athletes in a year — that was Saban’s first season in Tuscaloosa — and signed 29 last year.

Giving out more than the allotted 25 scholarships, or having more than 85 signed players following National Signing Day is what’s become known as oversigning. It’s a problem that’s been around as long as college football, and even before the implementation of current scholarship limitations, but the epidemic has picked up significant steam over the past few years thanks to the scrutiny disseminated by the 24/7 news feed of bloggers and the mainstream media.

Signing more than 25 players a year adds up fast over a four-year span, especially in the cases in which a program isn’t losing 25 scholarship players each season.

From 2005 to 2008, Kansas State signed 26, 30, 34 and 33 student-athletes in that span, which totals 123 scholarships. Of the 123 signed, at least 38 either won’t make it to campus or won’t finish out their four years of eligibility with the Wildcats.

So what happens to those student athletes? That’s where “roster management” comes into play.

Some players are given medical hardships, which keep them under scholarship but off the football team and not counting against the school’s total. Some are asked by the school to wait a semester or more for their scholarship, a practice known as grayshirting. Some flunk out. Others are flat-out dismissed for various reasons. Whatever the case, as long as a given program has 85 or fewer scholarship athletes by the time a season begins, it is in compliance with the NCAA.

But what about the kid who chose the school, then suddenly doesn’t have a scholarship? That is the heart of the issue of oversigning. It’s why the SEC recently adopted stricter bylaws for its constitution regarding oversigning. It’s why the media has become more aware of the issue. It’s why blogs such as the popular Oversigning.com exist.

The SEC

The Southeastern Conference has long been a target of oversigning criticism. Some of its schools have been the most abusive when it comes to promising scholarships it doesn’t have room to give.

Alabama’s oversigning history dates back to the 1920s, a decade before the SEC was formed. In 1941, William Bradford Huie wrote an article for Colliers Weekly Magazine documenting the Crimson Tide’s oversigning tactics. In a 15-year span, the Tide hoarded more than 1,500 student-athletes, mostly within state, and provided them with a hope of one day playing at Alabama.

Huie, an Alabama graduate and former university employee who said the Tides’ practices led to him no longer being a fan of college football, states Alabama ran hundreds of players off either by flunking them out or forcing them to quit.

In 1963, Georgia Tech left the SEC because of the oversigning practices of its rival schools — mainly Bear Bryant and Alabama. Yellow Jackets coach Bobby Dodd charged that Alabama was oversigning players and held “tryout camps” in the offseason, according to Jack Wilkinson’s biography titled “Dodd’s Luck.” Dodd urged the SEC to create a rule prohibiting tryout camps, and when the rule was voted down, the Jackets left the conference.

But Alabama isn’t the only SEC school accused of abusing scholarship limits. Ole Miss, Auburn and Mississippi State have all been criticized for recruiting malpractices.

However, there are SEC schools that are outspoken in regard to oversigning, including Georgia and Florida. Only twice in the Mark Richt era has Georgia signed more than 25 student-athletes in a given year. Since 2002, Vanderbilt has never signed more than 25 in one year.

“You can check coach Richt’s history here,” Bulldogs athletic director Greg McGarity said. “Before this became a national issue, Mark has made it a point to not oversign players. He’s always been upfront about the whole recruiting process.”

The controversy reached its boiling point in June, when at the SEC spring meetings conference athletic directors voted in favor of strengthening rules regarding the signing of student-athletes. Previously, the SEC allowed its schools to sign up to 28 student-athletes in a year. The revision, which will go into effect Aug. 1, reduces that number to 25.

“(The SEC) decided to bring (the issue of oversigning) to the forefront,” McGarity said. “We’ve put measures in place, and (Georgia) has always been as proactive as we can.

“(The amendments) are reactive to what other schools are doing.”

One of the criticisms of the new bylaws is that the number “25” is a soft cap, meaning teams will still be allowed to back-count early-enrolling signees to the previous year’s total if the 25 limit was not reached.

“There is wiggle room,” said Eric Bumgaurtner, associate athletic director for compliance at Georgia. “The perception is (an SEC program) could still oversign based on seniors and scholarships available.

“That’s not a concern, that’s a reality.”

Nonetheless, the recent measures taken by the SEC could be perceived as a step in the right direction. The SEC is the only major conference other than the Big Ten to have additional rules in its constitution designed to enhance NCAA limitations. All other FBS conferences defer to the NCAA. The SEC sent a proposal to the NCAA recommending the organization amend its constitution to conform to the new SEC bylaws.

In addition, University of Georgia President Michael Adams said the issue of athletic scholarships being one-year renewals will be addressed at a presidential retreat Aug. 9-10 in Indianapolis. Adams wouldn’t comment specifically on his thoughts of extending a scholarship to four years, but offered some insight.

“There needs to be a definition on what a scholarship is,” Adams said. “Not just if its 1-4 years, but costs as far as tuition fees, room and boarding, and so on.”

Adams also said there’s no reason a student-athlete should be left to fend for himself in the event his scholarship is rescinded.

“Sometimes in life you just do something because it’s right,” Adams said. “To offer an 18-year-old kid a scholarship and pull it away at the last minute leaves him with no options. It’s hard to understand why having 85 players isn’t enough to begin with. In the pros, they play 16 games with (53) players and a practice squad.”

The Big Ten

Before the days of the Internet and 24/7 news cycle, when football programs encountered less scrutiny for unethical practices, the Big Ten had already identified oversigning as a major concern.

In 1956, the conference ratified a rule limiting its schools to an 85-scholarship hard cap, meaning under no circumstances could a program sign players in excess of the NCAA’s limit of 85. If a team had 85 players on scholarship and only lost 10 players after the season, it could only sign 10 players in the incoming recruiting class.

The bylaw was amended in 2002 to allow schools to exceed the limit by three. To do so, the school must provide documentation to the conference explaining how it got down to 85 by the start of the season.

“The reason the rule is there is simple — don’t offer what you don’t have to give,” said Chad Hawley, Big Ten associate commissioner for compliance. “What our rule does is make (a member) institution really plan ahead to get a solid handle on the number of available scholarships leading into an upcoming academic year. Institutes must evaluate each student athlete’s eligibility; see who’s transferring, going pro or just leaving the program, and who’s financial aid will not be renewed.

“Once they go through that process and determine the slots they have available, they can offer three over.”

Sure enough, the results fall into place when it comes to Signing Day and the Big Ten. From 2002-2010, were just three instances in which a program signed 28 players.

In the same time frame, the SEC signed or exceeded 28 players on 34 different occasions. Only Florida and Vanderbilt stayed under the number 28 each year.

When asked if other conferences such as the SEC enjoy a competitive advantage due to its signing practices, Hawley offers an analogy.

“If you’re playing five-card stud, you deal me five cards, but the other guy is getting eight and picking his best five, that’s a disadvantage,” he said. “We haven’t focused (on what other conferences are doing) as a conference, but everyone acknowledges there’s a competitive element involved.”

With the SEC proposing its soft cap rules be implemented by the NCAA , Hawley said it could prompt Big Ten officials to consider proposing it hard cap rules to the NCAA.

“We haven’t discussed it as a conference,” Hawley said, “but if the SEC submits legislation, it does give us an opportunity to possibly offer our model as an alternative.”

McGarity said he wouldn’t mind if the Big Ten’s hard cap was made NCAA law.

“Sure, why not?” McGarity said.

For legislation submitted by a given conference to be put into NCAA law, it must be passed by the majority vote of the 31-members of the legislative council. The council consists of athletics administrators, faculty athletics representatives and institutional administrators, with one each from the 31 Division I conferences.

Any new legislation presented to the legislative council would be voted on at its Convention Meeting in January of 2012.

High schools

Before a student-athlete steps onto a college campus to play football on scholarship, he must sign a letter of intent. Leading up to signing day, prospects often make verbal commitments, which they can back out of at the last second. That can leave a school on the short end of the stick, even though it may have properly budgeted its allotted scholarships.

This is the other side of college recruiting, in which the school — not the student — is the victim. It could be argued, as a result, that a school may merely oversign to cover its bases.

“I think colleges are just trying to keep up,” White County football coach Bill Ballard said. “Most college coaches are honorable and are trying to do the best they can. There’s not a school in the country that doesn’t offer more (scholarships) than they have.”

Flowery Branch coach Lee Shaw also has an open-minded perspective on oversigning.

“Commitments and offers are coming earlier and earlier each year,” Shaw said. “The press is covering every step, then you have coaches changing in and out, kids not sure if that’s what they really want to do on their commitment — it’s a big game is what it is.

“I hate to say it, but there’s not much loyalty within offers or commitments.”

While it’s true schools can be left vulnerable when a student-athlete changes his commitment, there’s no question it’s the student-athlete who has more to lose when he becomes an oversigning victim.

A school can fill a void with a walk-on or another recruit the following year. However, if a student-athlete has his scholarship rescinded as a result of oversigning, he’s left with fewer options.

Chaz Cheeks, a recent East Hall graduate who signed with Georgia Tech, said concerns of oversigning factored into him eliminating Ole Miss from his list of school choices.

“(East Hall football coach Bryan Gray) and I sat down and looked at all of the offers on the table, the pros and cons of each school,” Cheeks said. “Coach said (Ole Miss) was throwing out offers to everyone, and they probably weren’t the best situation for me to go into. Having a spot wasn’t something I wanted to worry about.”

Cheeks said he had greater concerns — like making sure he was academically eligible to attend college — than to have to worry about if his offer still stood once he made it to campus.

“I was just thinking of myself and what I had to do,” Cheeks said. “For those that do get oversigned and have to be let go, I think that’s real messed up on the school’s part. They’ve got to be more careful.”

Gray said he has the same conversation he had with Cheeks regarding oversigning with all of his kids.

“We always keep an eye on that,” Gray said. “We gauge the school’s interest. I always ask (recruiting schools) what they see in my kid’s future. If they say something like 'redshirt,' that’s automatically a red flag. If they’re already thinking redshirt before the kid is even on campus, that generally tells me they have ulterior thoughts about getting as many kids as they can.”

Along the lines of a school’s intentions regarding a recruit, McGarity believes it’s critical the student-athlete and school know exactly where the other stands.

“It all boils down to communication,” McGarity said. “Everyone has got to be on the same page.”

Follow Adam Krohn at Twitter.com/gtimesakrohn.