0629fairstreetAUD

Listen to former Fair Street football star Gene Carrithers reminisce about the Tigers' titles.On the hard dirt of the Atlanta Street housing projects, they became a team. On the field at City Park, they became champions.

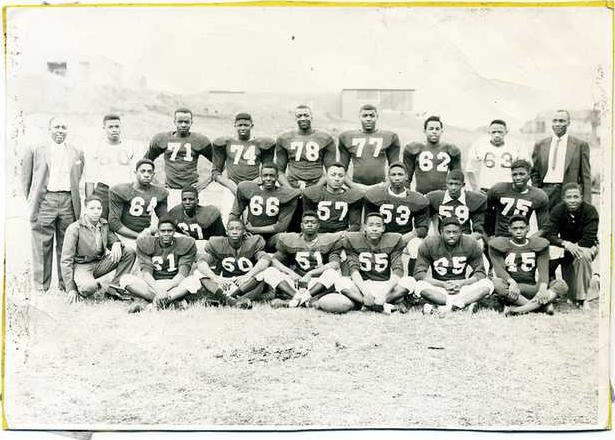

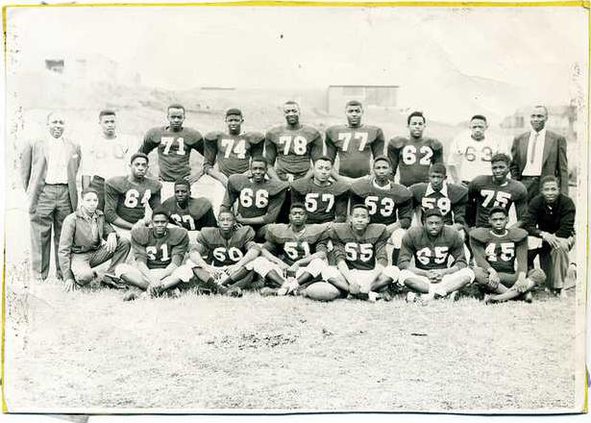

The 1956 and 1957 Fair Street Tigers were unlike many other football teams of their day. On offense, they ran the ball with speed and power and incorporated trick plays like the "flying trapeze."

Their defense was dominant, holding many opponents scoreless in a two-year span that included the Class B state title in 1956 and the Class A title in 1957. To this day, they remain the only Hall County high school to win back-to-back football championships.

They were champions. And off the field, in a time when Gainesville was still segregated, they were the talk of the town.

"In the black community, that’s all they talked about," said Gene Carrithers, a star running back on the Tigers’ championship teams. "All them folks closed up shop for the football games."

While they didn’t necessarily close down the town to attend games, the white community would also come out and watch the Tigers play.

"God, they were good," said Walt Snelling, who played football for Gainesville High in the 1953-54 seasons. "They were exciting to watch. They had some unbelievable athletes."

Those unbelievable athletes included Carrithers, who Snelling called "as fine a running back as I’ve seen in my life," Clifford Stephens and Ellis Cantrell also carried the ball for the Tigers during their championship seasons. Quarterback Cecil Young ran the offense, which included receivers Arthur Moss and Eddie Strickland and an offensive line containing John Keith and Clarence Niles.

"(Fair Street) had very good teams," said Jack Bell a member of the 1956-57 Gainesville Red Elephants. "They were upbeat and were more wide-open than the white guys were at that time.

"They had good, non-boring offenses," Bell added. "I guess you could say they were ahead of their time."

The birth of a team

According to Carrithers, when not spending their free time shooting pool, the members of the Fair Street Tigers were doing what they loved to do: Play football.

That time spent playing football for fun would ultimately be the reason that the Tigers won two straight championships.

"We grew up playing football out there on that hard dirt," Carrithers said. "That’s where we got good at it. It was the way of life. There was nowhere else to go and nothing else to do.

"Once we got into high school we had already been playing," he said. "From day one it just fell into place.""We had the team before the coaches got here," Cantrell said. "We were already a football team."

But though they were already a team, they were yet to be champions.

The road to the first title

Winners of their first four games of the 1956 season, the Tigers already had proved head coach E.L. Cabbell wrong.

Cabbell, whose wearabouts now are unknown to both Carrithers and Cantrell, but who they called a "hell of a coach," stated that the team needed "a lot of work" prior to the 1956 season.

But they didn’t. During its four-game winning streak that started the ‘56 season, Fair Street was unstoppable. The Tigers outscored their first four opponents 98-0 and had positioned themselves as a team poised for a state championship.

But there was one hurdle that the Tigers had to cross. In the fifth game of the ’56 season they had to play against Cedartown, a team that had never lost to the Tigers.

"We had some good football players at Fair Street," Cantrell said. "But they could never beat Cedartown."

"That was the best game I ever played," Carrithers said of the Cedartown game. "It was tough. It was a hard game."

A hard game in which Fair Street prevailed 6-0.

With Cedartown out of the way, the Tigers continued their winning ways. In subsequent weeks, they beat Lithonia 41-0, Jackson 46-18 and Elberton 27-13 on homecoming night.

Their season was flawless. But while they steam rolled the majority of the competition, the Tigers were still dealing with the strife of living in a white man’s world.

The tie that binds, and breaks

Scan the crowd during a Fair Street game at City Park and there would be people from all walks of life, including members of the white community.

"We had good crowds," Carrithers said. "We had whites and blacks."

According to Bell, the attendance at the games was in large part due to the Tigers’ entertaining style of play, and the fact that social opportunities were scarce.

"They had a good group of people come to the games because there really wasn’t that much to do," he said.

But even at their own games, Fair Street’s black fans, like the students of Fair Street themselves, were segregated.

"Whites really owned the place, so we had to get where we could get," Cantrell said.

That attitude resonated outside of the football stadium.

"Everywhere you go, you’re black," Carrithers said. "Back then, they said this is where you went and this is where you didn’t."

Added Cantrell, "There’s some things you could do and there’s some things you didn’t do. That’s just how it was.

"I remember my wife telling me about a time she went into an old drug store that was known for having good hot dogs, but it was a white drug store. She went in there and asked for two hot dogs. They looked right at her and said, ‘Two dogs walking.’ She could get food there, but she couldn’t eat there."

‘A sad night’

Weighing 133 pounds during his playing days, Carrithers was used to taking a beating on the football field.

"They used to put it on me," he remembered. "I was marked everywhere I went."

While getting physically pounded was familiar to Carrithers, what he and the rest of the Tigers weren’t used to is losing. Which is what happened Nov. 2 to Greensboro during the 1956 season.

"That was a sad night for some players," Cantrell said of the 6-0 loss to Greensboro. "But that was my best night. I played the best I could do. I couldn’t have done more. I gave 110 percent.

"We could have won the game, but I don’t think everybody gave 100 percent," he added. "That’s why I was mad."

According to Carrithers, the physical nature of the game may have influenced the outcome of the game. "Our team got scared because they were hitting hard," he said.

After that loss, that group of Fair Street Tigers never lost again.

Crowning a champion

In the locker room after the Greensboro loss, some members of the Tigers cried. But those emotions soon turned to motivation. The loss fueled the Tigers’ desire to win a state championship, and never lose again.

"It kind of brought us together," Carrithers said. "It showed us that we can be beat. We went on to win 21 straight games after that."

Including their first state championship.

On Dec. 9 on a muddy City Park field, Carrithers and Cantrell each scored a touchdown and Young contributed with two touchdowns, one passing and one rushing, as Fair Street cruised to a 27-0 win over the Evans County Longhorns.

"That was the best one because it was the first one we’d ever one," Carrithers said. "Everybody had us favored in that game."

The Tigers proved why they were the favorites and after the game, they celebrated.

"That’s the first drunk we got," Carrithers said with a laugh.

Racial tension in the South

Less than a year after Fair Street hoisted its first state championship trophy, the fight for integration came full tilt.

As the Tigers were preparing to defend their title, a group of white students in Little Rock, Ark., were preparing to block the doorways of Central High to prevent nine black students from being admitted.

After being escorted into the school on Sept. 20 1957, the "Little Rock Nine," as they would eventually be called, were subject to physical and verbal abuse throughout the school year.

More than 575 miles away, Gainesville remained segregated.

Three years had passed since the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled all laws establishing segregated schools to be unconstitutional in Brown vs. Board of Education. Cities throughout the South were feeling the strains of forced integration, but Gainesville remained divided.

"We pretty much stayed in our community," Bell said.

Added Snelling: "They were doing their thing and we were doing our thing."

Sweet revenge

The Fair Street Tigers began the 1957 season the way they ended the 1956 season, with nothing but wins. Despite moving up a classification, the Tigers shut out five of their first six opponents and outscored the competition 158-14.

"We knew we still had a team in ’57," Cantrell said.

But like the previous year, the Tigers had to overcome one obstacle en route to the state title. In 1956, it was Cedartown; in 1957, it was Greensboro, the last team to send the Tigers off the field as losers.

Remembering what it was like the last time they lost, Carrithers took the game’s opening kickoff 80 yards for a touchdown and the Tigers went on to win 20-6.

"After that we knew we were going to beat everybody else," Cantrell said. "We knew we were going all the way."

Simplicity wins a championship

The Tigers were known for their creative offensive plays, the most famous being the "Flying Trapeze."

On that play, Young would pass the ball to Moss, who in turn lateraled the ball to either Stephens or Carrithers, and they would race down the field untouched for a touchdown.

"Mr. (Ernest) Tolbert put that play in," Cantrell said. "Moss and Clifford (Stephens) made that famous."

"I just came in on the end of it," Carrithers said with a laugh.

While the Flying Trapeze was the highlight play for the Tigers, and one they used often, it was a simple running play that propelled them to the 1957 Class A State Championship.

With the score tied 7-7 with six minutes to play in the game against Thomasville, and the ball at the Fair Street 41-yard line, the play "24 Quickie" was called in from the sideline.

Carrithers took the handoff and scampered 32 yards to put the Tigers in scoring range.

"Big Niles opened it," Carrithers said, referring to the hole in the offensive line that lineman Clarence Niles provided. "I just hit to the left, and once I got in front, you weren’t going to catch me."

Five plays later, Carrithers scored the game-winning touchdown.

"Winning that second state championship did something for me," Cantrell said. "It made me say I was the best."

The Tigers were the best in regards to the black schools in Georgia, but to this day, they still are unsure if they were they best team in their own town.

An uncontested rivalry

The Gainesville Red Elephants and Fair Street Tigers supported each other. When they could, they would attend each other’s games and cheer them on.

"There weren’t too many times we could see one another play," Bell said.

The stands were the closest that the two teams would ever come to being on the same field at the same time. But that didn’t stop the Tigers from dreaming about playing their crosstown counterparts.

"Back then, even though we knew that Gainesville High was better coached and probably bigger, we thought we might be able to beat them," Cantrell said. "We would have liked to have tried anyway.

"That wasn’t possible," he added. "But we would have liked to have tried."

Cantrell’s partner in the backfield echoed that sentiment.

"We wanted to play Gainesville High because we thought we could beat Gainesville High," Carrithers said.

Though not truly knowing how the game would play out, Gainesville’s Bell thinks that Fair Street might have come out the victors.

"They had a better football team then we had," he said.

Twelve years after the Fair Street Tigers celebrated their second championship, Gainesville’s city schools integrated. The black students who went to Fair Street and E.E. Butler high schools were enrolled at Gainesville High. The two football teams became one.

In 1956 and ’57, that thought never crossed the minds of the players. But in retrospect, if that were to have occurred earlier, who knows what would have transpired?

"That would have been something," Carrithers said of playing alongside Gainesville’s players. "Makes you think about it and wonder what could have been."

Snelling knows what would have happened.

"If we would have played together, we would have been world beaters," he said.

Teammates for years, friends for life

The games played for Fair Street High are mere memories for the members of the back-to-back championship teams. But more than 52 years after they last took the field together, the Tigers remain friends.

Young, Cantrell, Carrithers and William Johnson all remain close. They talk on the phone, and when he can, Carrithers makes the four-hour trek from his home in Albany to visit his former teammates.

A year younger than the rest of his teammates, Carrithers played football during the 1958 season and was injured in his final game against Cedartown, a game in which the Tigers lost.

"Cedartown stood me up and a guy came in and hit me," Carrithers said of hit. "I’d get hit like that all the time, and most of the times on I’d lay on the ground and pretend I was hurt. That time I never got up."

He never got up, and aside from playing flag football while in the Army, he never played football again.

"I believe I probably could have made it if times were like they are now," Carrithers said of playing college football. "They didn’t recognize us. We had a good team, and a lot of them could have played in college."

With no college scholarships available at the time, the players were forced to hang up their cleats and pads and join the workforce or military service.

Both Carrithers and Cantrell joined the Army, and although Cantrell attended his son’s games at City Park, neither has stepped foot on the field since they graduated high school.

The games may now be memories, some of which our forgotten, but the bond they created during their championship runs will never cease. And, despite what the times were like in 1956 and ’57, no one will ever be able to take away the fact that they always will be champions.

"Those two titles are something I’ll carry with me throughout my life," Cantrell said. "A lot of people play football, but not everybody don’t win a state championship.

"You don’t be the best," he added. "You might want to be the best, but you don’t be.

"We were the very best, and that won’t ever be taken from me."