Hall County Superintendent Will Schofield's stately home is surrounded by 12 acres of field and forest, a small organic garden and a young orchard.

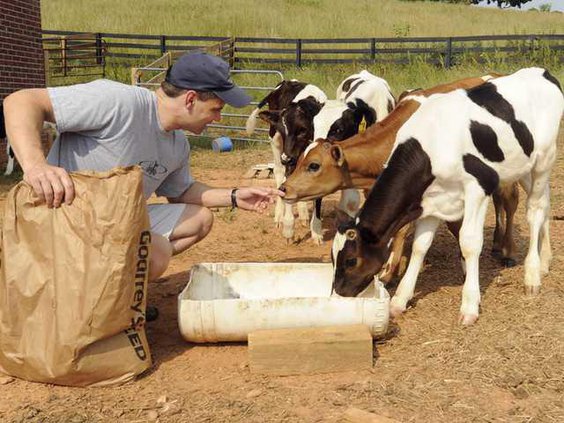

And, of course, the family's dairy calves.

"This was our dream when we came back. We wanted to find a place where we could have some animals," Schofield said. "We cleaned it up and planted it and fenced it, and we've got what we affectionately call — it's a bit of a stretch — our little farm."

Schofield said the family began raising dairy calves about 18 months ago.

"There is nothing more beautiful to me than being able to look out my window and see this," Schofield's wife, Joy, said.

The nine calves on the little farm now belong to the Schofield kids as a way for them to earn money and learn life's sometimes difficult lessons.

"The kids do some meaningful work and get to see what happens when you put some effort into something," Schofield said. "They put a little bit of money in a calf and sometimes it dies, and that's real life. Sometimes you sell it and make a little money."

The Schofields purchase their calves from Truelove Dairy.

The females are sold in the spring when they are old enough and the males when they reach between 1,100 and 1,200 pounds.

Sometimes family friends buy the calves as grass-fed beef, but if not, the animals are sold to a sale barn.

Sarah, David and Hannah, ages 15, 14 and 7, take turns feeding the calves twice a day and help with routine calf management jobs such as dehorning and castrating, which Schofield — a seventh-generation dairyman — did as a child on his father's farm.

"My father bought our dairy farm (north of Green Bay, Wis.) the year I was born, but we lived in Milwaukee," Schofield said. "We were city kids. I was probably 8 years old when my dad announced to us at dinner one night, ‘Kids, I've made a decision. I sold my medical practice and we're moving to the dairy farm.'

"My brother and I cheered and my sister cried, but we moved up to the dairy farm and for the next 10 years we farmed together as a family."

The family kept the dairy until Schofield graduated from high school, when his father decided it was time to start practicing medicine again.

But that didn't stop Schofield from wanting to farm.

He was a college freshman at the University of Wisconsin in 1982 when his parents moved to Athens.

"I came down Christmas vacation," Schofield said. "It was 40-below zero when I left, and 70 above when I got to Athens. Everyone was in T-shirts. I called my roommates and said, ‘I'm not coming back.'"

Schofield enrolled at the University of Georgia and dove headfirst into the region's dairy industry.

"I had a 200-cow dairy of my own that I ran in Oglethorpe County while I was going through college," he said.

He also managed another 300-cow herd.

"It was kind of a dream job," Schofield said. "The first two years I taught, I had a dairy of my own and milked cows of my own."

It's something he says is simply in his genes. Schofield is descended from Wisconsin farmers who immigrated in the late 1800s. His maternal grandfather sold some of the first electric milking machines on the market. His paternal grandfather and father both ran milk truck routes in northern Wisconsin.

Teaching, unlike agriculture, was something Schofield never considered a career goal.

After spending a day with a math teacher friend in Oglethorpe County, Schofield went to Aderhold Hall on the UGA campus and changed his major from math and computer science to math education.

"I started teaching in 1986 in Oglethorpe County," Schofield said. "I taught math in high school and coached wrestling and football."

It wasn't until three years later that Schofield became serious about teaching. His path to Hall County started with a terrible accident and a year of pain.

The first memory Schofield has of May 1, 1989, is waking up in an emergency room with nurses peering over him, wondering if he would survive.

He had flown to Idaho to investigate a potential law school, and was on his way back to Athens from the Atlanta airport when he was hit head-on by a man driving 60 miles per hour in the wrong direction.

The accident changed his life.

"Over the next several days, I had a series of back surgeries and foot surgeries and chin and elbow surgeries, with the orthopedist saying, ‘I'm not sure you'll ever walk again,'" Schofield said. "It was during that six months to a year, laying flat on my back and going from a wheelchair to walker to crutches, I realized whatever days I had left I was going to spend in education."

In 1992, Schofield moved to Social Circle and served as an assistant principal, then principal. He came to Hall County and was principal at West Hall High School, then returned to Social Circle in the late '90s to serve as superintendent for four years.

"When the kids were young - Sarah was in first grade, Hannah wasn't even born yet and David was a kindergartner - we decided if we ever wanted to have an out West experience, now was the time," Schofield said. "I took a superintendent's job in Boseman, Mont. I stayed out there two years."

When the Hall County superintendent job opened, Schofield was invited back.

This time around, he decided the best way to teach his kids was not in the classroom, but in the field.

And it seems to be paying off — Schofield predicts David is going to be a dairyman.

"He actually gets it," he said. "There's something about being able to walk through a herd of cows and be able to see when one isn't feeling well. He's got the instinct. Maybe he'll be the eighth generation."

Joy said one of David's calves, Susie, follows him around just like a dog.

"No joke, she'll lay on top of him. He calls her like a puppy, and she comes," Joy said. "When it snowed, David would go down the hill, Susie would go down, the dogs would go down. David comes up, Susie came up and the dogs came up."

It's a lifestyle Schofield said he is blessed to have.

"It's like a therapy for me. There are no challenges," he said. "Some people golf, some play tennis, and some go on trips. We go out here and work."