Nov. 22, 1963, started off like any other fall day for Bimbo Brewer. For the University of Georgia freshman, it meant another day of classes.

That day ended with Brewer and his fellow journalists in Gainesville covering one of the biggest news stories of the century: The assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

That afternoon, he was sitting in his abnormal psychology class watching a movie when a knock was heard on the door. The professor answered and stepped outside.

A few words were exchanged and the professor returned to the classroom, turned on the lights and announced that class was canceled. Judging by the man’s tears, the students thought a family member had died and quietly filed out.

Brewer and a friend walked away from North Campus, toward The Varsity. They could see a congestion of people and cars outside the popular eatery.

“Susie, someone’s been hit by a car,” Brewer told his friend.

As they drew closer, they discovered that what had stopped traffic — both pedestrian and automobile — were accounts of the national news story unfolding on three televisions inside The Varsity. Like a child’s game of telephone, details filtered from one person to the next through the throng of people there and left Brewer in disbelief when it reached him in the back of the crowd.

President Kennedy had been shot.

“‘He’s dead!’” Brewer said one man recounted.

“No, he’s not dead yet!” another said.

Brewer said his friend turned to him, asking “‘What are you going to do?’”

Brewer, who worked part-time at The Times in his hometown of Gainesville as a journalism co-op student, started walking back to the boarding house where he lived. He saw his then-girlfriend, Nancy Martin, driving down the street toward him, honking the horn and waving at him.

“Get in!” Nancy yelled at him. “You’ve got to go home. The paper called and you’ve got to go in.”

Breaking the news

In 1963, The Times’ newsroom, like many others, was equipped with a teletype machine that acted almost like an automatic typewriter to give newsrooms stories sent from wire services. When really important news was being sent, a series of bells would sound. Three bells meant urgent and five bells was a bulletin. Ten bells was a flash, but no one at The Times had heard 10 bells before.

Until Nov. 22, 1963.

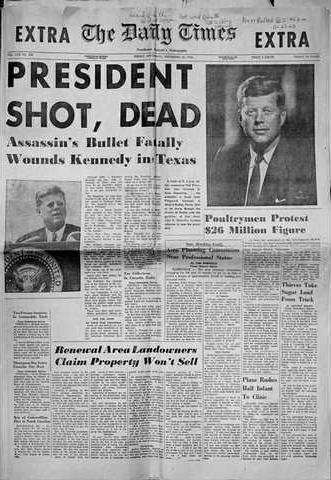

Friday’s edition of The Times was rolling on the presses, with front page stories ranging from coverage of international poultry negotiations to a short notice about the dedication of E.E. Butler High School that was planned for that Sunday. There even was a small item about President Kennedy talking about the U.S. testing a rocket booster, putting them ahead of the Russians in the space race.

With deadline over for the day and no Saturday paper to work on, most of the staff was gone that November afternoon. Managing Editor Johnny Vardeman and few others remained in the newsroom at the paper’s Spring Street offices.

He was in the newsroom when he heard the first sounds from the teletype.

Three bells. Urgent.

Vardeman checked the teletype machine to find a report that shots had been fired in Dallas, Texas, where the Kennedys were visiting. Soon after, he heard five bells: a bulletin.

Kennedy and Gov. John Connally of Texas had been hit by shots.

Someone stopped the presses and the Times staff scurried to get the front page remade to feature the story that Kennedy had been shot.

“We had to wait on enough information from the wire for a story,” Vardeman recalled. He explained the task of setting “hot type” in those days meant it was a cumbersome task to change a front page and not a very fast one.

“Nine lines a minute was fast on a linotype machine,” he said.

Then, a little after 2 p.m., the flash — 10 bells — came across the teletype machine at The Times and news organizations around the world.

President Kennedy was dead.

Extra edition sold quickly

The presses started rolling on the Times’ extra edition at 2:45 p.m., less than an hour after the announcement of Kennedy’s death. By 3 p.m., the 5,000 copies were sold on the street by carriers and newspaper employees. They quickly sold out.

Vardeman recalled that he was told that The Times was among the earliest of newspapers to get the news out on the streets that Kennedy had been assassinated, but he has no way of verifying that.

Part of history

Brewer and Martin, who would be married the following year, heard the news of Kennedy’s death on AM radio as they were driving to Gainesville. Brewer went straight to The Times and wouldn’t see Martin for another week.

And for several days, Brewer said he didn’t leave the paper save to gather and report more local reaction on the assassination. Meals and sleep would be grabbed in snatches at the office, Brewer said. The days passed in a blur.

Sylvan Meyer, then editor of The Times, realized as he was guiding the paper’s coverage of the story that it was a moment in history, Brewer said.

“‘I wonder if they understand that they’re players in a part of history,’” Brewer recalls overhearing Meyer tell a colleague about his staff.

Brewer said hearing those words made him realize the task that had been handed to him.

“I realized that we were mandated to be a part of history,” he said. “There were thousands of stories in the nation and the world, but the most important ones were right there with us.”

When asked recently, both Brewer and Vardeman agreed there was little time over the next few days to stop and contemplate their own feelings about Kennedy’s assassination.

“We probably had a little breathing room to collect our thoughts and make assignments,” said Vardeman, who later served as editor and is now retired. “We also were busy with just routine stuff then, trying to get everything (else) covered.”

It would be days before The Times, and the community, would get back to coverage of the football playoffs and the Belles of the Ball. But things had been changed forever.

Brewer, who today is director of the Victim-Witness Assistance Program for the Hall County Sheriff’s Office, said his perception of being a journalist changed from fun and games into serious business.

“I changed my reporter shoes that day when I got in Nancy’s car and I never got to put the others back on,” he said.