Maj. Kevin Jarrard is finally home.

Despite being in the United States at Camp Lejeune, N.C., for about a week, he didn't feel truly at home until he reached the house in North Hall that he built with his own hands.

Eight days ago, at a train station in Montgomery, Ala., he was reunited for the first time in months with his wife, Kelly, and their four children.

He said their collective embrace lasted quite a while. "Fourteen months is a long time," Jarrard said.

He was able to keep a promise that he made when he left last May with his Marine Corps Reserve unit, Lima Company, 3rd Battalion, 23rd Marines, based in Montgomery.

"I went by and shook the hands of all those mamas and daddies and wives and girlfriends and told them I'd do the best I could to bring their boys home safe. Knowing what has happened over there (Iraq) in the past few years, I felt pretty sure I wouldn't be able to do that," he said. But he did.

"It was huge load off of my shoulders," he said. "Nobody was wounded or killed in our rifle company."

Last Friday night in Montgomery, they held a thanksgiving service, something Jarrard had feared beforehand would be a memorial service.

Thursday night, Jarrard returned to Montgomery after spending a few days at home. He still has to wrap up some administrative responsibilities of his command following the end of his unit's deployment to Haditha. Jarrard, who just completed his second tour of duty in Iraq, won't be returning there unless his unit is recalled.

A tall, slender man, Jarrard looks like a Marine, even out of uniform. His soft-spoken, deep voice comes out in crisp tones. And he adores his children. During an interview with The Times, the children sat quietly on the sofa with him, touching him periodically as if they were reassuring themselves that dad is really home.

He is a complex man. He is a solid soldier who treats a day of hunting for terrorists and explosive devices in an Iraqi city as just another day at the office.

A father of four, Jarrard also is a man with a special place in his heart for children. Deeply grounded in his Christian faith, Jarrard quotes Moses, someone who knew a thing or two about leading people in the desert.

"‘Take heed to yourselves, lest you forget what your eyes have seen,'" Jarrard said, repeating the words of Moses from a verse from the Old Testament book of Deuteronomy.

He saw a lot in Haditha, an Iraqi town of about 90,000. However, nothing touched him more than ailing children, whose lives were in jeopardy without surgery not available in Iraq.

At Christmas, Jarrard began contacting friends at home about the plight of Amenah, a little girl who was born with a severe heart condition. He thought of the example his father, Tom, a Gainesville attorney who died of cancer just as Kevin was preparing to leave for Iraq last year.

"Dad didn't talk about helping folks, he just did it," Kevin said. "It was always a family affair. We'd just get in the truck and just did stuff."

John Nadeau, a Navy doctor from Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., arranged for Amenah to receive care there without cost. Money was raised for air fare for Amenah, her mother and a medical support person.

Jarrard, recognizing the severity of her condition, cautioned that she might not survive the trip or the surgery. "It was touch and go," Jarrard said.

He rode with the girl and her mother to the Iraqi border in a helicopter and was afraid the girl was dying. She required oxygen while in flight to the United States and was placed in an intensive-care unit upon arrival at Vanderbilt.

Doctors prescribed antibiotics for an infection she developed and it was more than a week before the surgery could take place. But the operation was a success and the little girl's blue lips and fingers were suddenly turned a robust pink.

Her story was reported on network newscasts and even drew the attention of President Bush; he met the surgeon, Karla Christian, who performed the life-saving, open-heart surgery.

"Some of the Marines raised money, and they sent this little girl, whose heart was ailing, to America, right here to Nashville," Bush said on a March 11 visit to Nashville. "And Karla and her team healed the little girl and she's back in Iraq. And the contrast couldn't be more vivid. We got people in Iraq who murder the innocent to achieve their political objectives - and we've got Americans who heal the broken hearts of little Iraqi girls."

During a recent visit to Iraq, GOP presidential candidate Arizona Sen. John McCain visited Haditha, and wanted to meet Amenah after having heard her story. Jarrard said he had to explain to his Iraqi friends who McCain was. "This guy could be the next president of the United States," he recalled telling them.

But his work didn't stop there. Jarrard, Nadeau and Navy Lt. Cmdr. James Lee decided to tackle the project of rebuilding the dilapidated Haditha hospital, the only facility in an area of 130,000 people.

Jarrard described the hospital as a sprawling, single-story facility that lacked modern equipment and didn't have air conditioning. Even if it did, it would have been hampered by the fact that many of the windows were previously blown out. "It looks like an old hospital we might see around here," Jarrard said.

The trio met with U.S. officials and tribal sheiks and received $4 million in U.S. support to repair the hospital.

As his command was drawing to an end, Jarrard successfully completed another humanitarian mission.

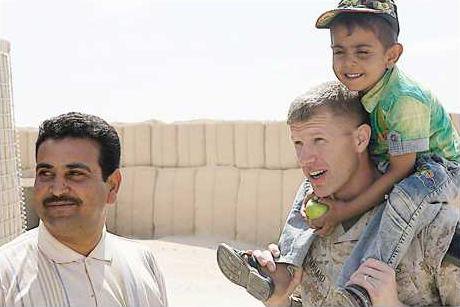

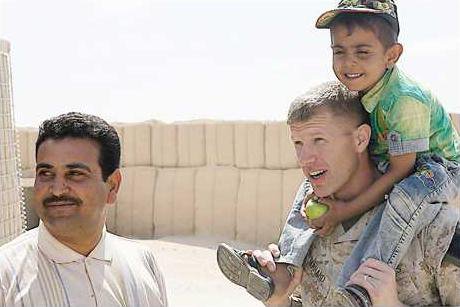

He had met an Iraqi police officer, Hammad Muhammad, with a 4-year-old son, Ammar. Like Amenah, the little boy had a heart defect. There was enough money left from the effort for Amenah to get Ammar and his dad to the U.S. "They left the day my command ended," Jarrard said.

Just 10 days ago, Jarrard left Camp Lejeune and traveled to Charleston, S.C., where he was reunited with Ammar and Hammad. Ammar's condition was corrected by surgery and Jarrard held the little boy in his lap for half an hour.

This week, the boy and his father safely returned to Iraq just as Jarrard was returning home to Gainesville.

While he is glad his tour of duty is over, he admits that the final weeks were a race against the clock. He envisions finding a way to help more children in the war-torn country.

In private life, Jarrard is a history teacher at Riverside Military Academy, where he looks forward to returning in the fall. Until then, Jarrard plans on take a family vacation with his wife and four children in May.