Stationed just outside Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam, Rudy Guerrero and his fellow Marines got the call to go to the U.S. embassy.

And hurry. Reinforcements were needed.

It was just the kind of duty he craved.

“I was always a hot dog, always wanted to do things,” the Gainesville man said.

Guerrero and his platoon were soon thrown into the frenzied chaos of evacuating the embassy as communist North Vietnamese troops were advancing on South Vietnam.

Thirty-five years ago today, Saigon would fall to its longtime enemy, the U.S. would flee in Huey helicopters and the communists would proceed to take over the Southeast Asia country, which they still rule.

The memories of his mission are still imprinted on Guerrero’s mind, a critical moment in U.S. history that was captured by TV news cameras. Americans at home watched as desperate South Vietnamese climbed aboard helicopters on the embassy’s roof.

Guerrero helped escort evacuees to waiting aircraft. But his other job was “to hold back the Vietnamese who tried to get ... inside the compound,” he said.

“I’ve seen stuff, but I’ve never seen desperate people so badly trying to get out of a place,” he said.

“I wasn’t expecting to see all this going on — people trying to kill each other to try to get into the compound, pushing each other against the fence, trying to jump over the fence. And here we are trying to hold them back.”

Soon after Saigon fell, the rest of South Vietnam capitulated. The new government renamed Saigon after communist revolutionary Ho Chi Minh.

The series of events further soured U.S. spirits.

America was not victorious in war, a new experience that “called into question many of the policies that put so many American soldiers into Vietnam,” said Chris Jespersen, history professor at North Georgia College & State University in Dahlonega.

“From the North Vietnamese perspective, Saigon was liberated,” he added.

“From the United States perspective, (the fall of Saigon) was more symbolic than anything else. The U.S. had pulled out militarily in 1973. There was no question as to what was going to happen, I think. There was only a question as to when it was going to happen.”

Jespersen has taught “a course on Vietnam more times than I can count,” has visited the country and is writing a book in which he compares the U.S. response in Vietnam to the British response during the American Revolution.

U.S. morale would further deteriorate in the 1970s, with economic woes, the energy crisis and revolutions in Nicaragua and Iran.

“You get a sense that America (was) on the retreat, so that when Ronald Reagan campaigns (for president) in 1980, he’s got a list of complaints,” Jespersen said.

And while the U.S. military rebounded, particularly in the Persian Gulf War of 1990-91, Jespersen doesn’t believe the U.S. has exorcised its Vietnam demons.

“I think it still resonates, in large part because so many of the people who lived through it, for whom it was a formative event, are still alive,” he said.

The memories still flood the Rev. Joe Tu, Vietnamese pastor at First Baptist Church on Green Street in Gainesville.

He grew up there and recalls vividly the violence and death that permeated his country.

Fleeing Da Nang with his family as the North Vietnamese advanced on South Vietnam, “I saw children dying on the streets, mothers crying because they lost their children ... a father wrapping (up) his dead baby and holding it to his shoulder,” Tu said.

“Those are my memories. And sometimes, even these days, while I’m driving, they are my tears. As I think about it, I just cry,” he said.

The fall of Saigon — all of Vietnam — was a shock to Tu, as well as family and neighbors.

The peace treaty of 1973 gave South Vietnamese hope that war was no more.

“It was a good feeling for everybody,” he said. “I had seen people hurting all the time. ... April 30, 1975 was something I’ll never forget.”

Eventually, he and his immediate family were able to escape the country by boat. They, along with about 8,000 other Vietnamese, were rescued by a U.S. cargo ship.

Tu has one stark memory from his time aboard the ship. The Vietnamese, following radio BBC reports, heard an announcer say, “The south is lost to the communists.”

“The whole ship was just quiet,” he said in a whisper, “for two days.”

The ship’s foreign passengers suddenly realized they might not be returning to their homes.

“They weren’t thinking they would come to America as refugees, live here and stay here,” Tu said.

The minister returned to Vietnam for the first time three years ago.

“I didn’t feel at home,” he said of his experience. “... They look at you like you’re Vietnamese but you are a foreigner. I felt lost.”

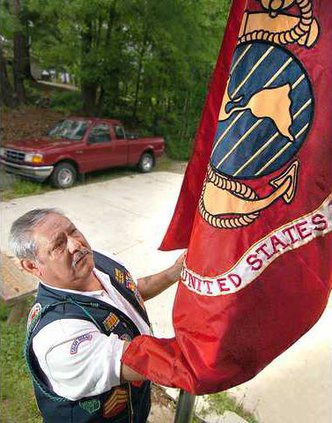

As for Guerrero, he never lost his devotion to the Marines. He has flags representing the U.S. and the Marine Corps waving atop a homemade, metal flag pole in front of his home off Memorial Park Drive.

He is also active in the Vietnam Veterans of America, Chapter 772, and the Marine Corps League, Upper Chattahoochee Detachment.

Guerrero hasn’t forgotten his call of duty on April 30, 1975, but it isn’t a chapter of life he dwells on, either.

“It was something we had to do. We were there to do a job,” he said.