Ninth-grade students in the Johnson International Scholars Academy got a crash course in forensics Wednesday, successfully solving a kidnapping.

The demonstration was part of a lesson given by members of the Bio-Bus team from Georgia State University.

The team, which usually arrives at schools with a bus-turned-science-lab, was able to expose students to a host of new possibilities.

In addition to seeing some of the programs at Georgia State, students also got the opportunity to do experiments they wouldn't otherwise see until possibly their sophomore year in college, said Maurice Willis, a Bio-Bus Fellow and medical school candidate.

"This gives them a taste and exposure to greater technology and consideration of possible careers in biotechnology, specifically forensics and exposure to real-life crime solving," said Alice Broxton, science department chairwoman and honors JISA biology teacher. "They're showing them the connections of biology, chemistry and physics. Anything we can do to relate it to their everyday life is always a good thing."

Physics, for example, can be connected to blood spatter patterns: Large spots of blood usually come from being hit at a low velocity such as with a lamp, while "freckled" spatter indicates being hit at a higher velocity, as with a beating.

Physics can also help scientists determine if a death is due to a suicide or foul play, depending on where the body lands from a building or bridge.

Geology comes into play when determining where a body or suspect has been. For example, if a body has red clay on it, that indicates it was probably in Georgia recently, Willis said.

The branch of science studying insects, entomology, can help investigators determine time of death as they look at bugs found on a dead body and what life cycle they may be in.

"We go to different schools all year round and talk about various fields of science," Willis said. "The whole purpose of this class is to show them the gel electrophoresis, the blood typing and how this is all a part of biotechnology."

The case, based on an actual crime, centered on a kidnapped girl named Dawn. Her mother, stepfather, boyfriend and best friend were the suspects.

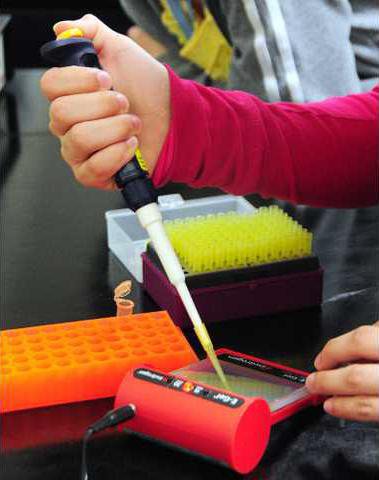

After examining crime scene photos and the ransom note, students got to work using gel electrophoresis, blood type analysis and fingerprint inspection to figure out whodunit.

During the gel electrophoresis experiment, students tried to match DNA from the suspects to DNA found at the crime scene. Because DNA molecules have a negative charge, the electrically charged gel separates it into bigger and smaller particles, allowing for a visible breakdown of the DNA match.

The fingerprint analysis let students use magnetic wands and metal shavings to see how every fingerprint is different. During the blood typing experiment, students added antigens to different blood droplets to see if suspects' blood was type AB, A, B or O.

At the end of the class, the experiments revealed the boyfriend was the kidnapper, but Willis said in the actual case, the best friend was also found to be the mastermind behind the plan.

Willis used to do autopsies with the Fulton County Medical Examiner's office, so he shared some of his experiences with students as he explained the crime-solving process.

Fingerprints come from a fetus touching its mother's womb, and the only ways to get rid of them involve third-degree burns, sulfuric acid or chopping your fingers off, he said. Even Mother Nature is against criminals, what with geology and entomology's involvement in forensics these days.

And when it comes to blood, bleach doesn't work. There's only one way to get rid of it, Willis said, but he wasn't going to share that with the students.

Alex Kimbrell, 15, said the forensics session was "way better than class."

Asher Griffith, 14, agreed.

"When you actually get to do that, it's cool," Asher said. "I think the fingerprinting thing is really cool, and the blood typing."

Asher said after Wednesday's lesson, forensics might be a neat career to look into in his future.