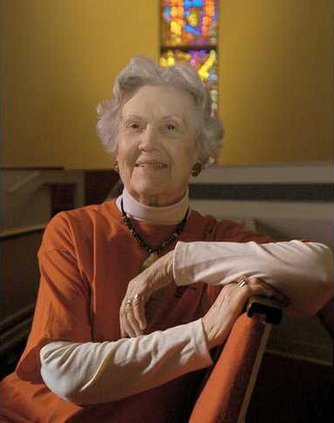

0129Landers

Frances Landers talks about how the first school in Haiti came to be.For some, it’s as simple as a monthly check to provide scholarships to school children. For others, it means packing your bags and heading out to Nicaragua or Zambia or Haiti.

And at First Presbyterian Church’s World Missions Conference this weekend in Gainesville, which aims to raise money and awareness about issues in developing countries, anyone interested in volunteering in missions can learn more and get involved.

Matt McGowan, former pastor at First Presbyterian, is organizing this eighth annual event. He said he hopes to raise $90,000 this year, and last year they even exceeded their goal by a few dollars.

"We hope to educate the people on the exciting opportunities for world evangelization. We want to inspire and motivate them," he said. "The interest in world evangelization is growing every year."

As a preview to the conference, Frances Landers, 91, spoke at the church last Wednesday. Her organization, the Haiti Education Foundation, is one of the recipients of money raised at the World Missions Conference.

She stressed that education is the most important issue facing the country, and her organization has been able to open more than 50 schools in the rural mountains of Haiti. As a result, more than 13,000 children now receive an education.

The full text of the Q&A with Frances Landers is below.

Question: Was Haiti a calling for you?

Answer: Well, it really almost just happened in that I live in El Dorado, Ark., and my husband’s an opthamologist, and we attended a meeting at our church in El Dorado, and the talk was about missions of the Presbyterian church all over the world. In his closing statement, he said, "And then we have this little hospital in Haiti. Our only hope of keeping it open is to get doctors to take their vacation time and come down and work." Well, with Gardner being an opthamologist, we thought, "Well, they really wouldn’t need us. They need internists and so on."

But his next statement was, "Our greatest need is opthamologists, because people in Haiti who have cataracts are blind for life unless they can get to a missions hospital when there’s a visiting doctor from the states." Now, we can’t use the word simple, but (cataract surgery) is more routine, and we thought, if people are really going blind from cataracts, blind for life, that’s something we can do. One of our sons is an opthamologist, and the three of us made the trip in 1977. We found this was true — that people were leading people in and all the problem was was cataracts.

So we developed a routine of going to Haiti twice a year, and we did that for 12 years. So that was our beginning, Hospital St. Croix in the village of Leopo.

As we worked in the hospital, we worked with an Episcopal priest, Jean Wilfrid Albert, and he continued to say to us, "Our only hope for Haiti is education. It doesn’t matter how many can see, if they can’t read and don’t have the advantages of an education, there will be no problems." So one day he asked me to go with him to a village that’s about five miles from the hospital, and he said, "I want you to see a village where no one can read or write. So we went out to the village and not only did people just wander around with blank stares, there was a voodoo priest in the center of the village, and he had his temple, and this is what the people were using. And he was the only person in the village that wasn’t hungry — they all brought their produce to him.

So, we realized this is true — education had to be the answer.

We came back to the states and asked our church in El Dorado if they would build a school in this village and they gave us the money to build a 10-room school, and we had 400 children. And we had the privilege during those 12 years of watching that school develop, and watching the lifestyle of the people in the village change. Because they were able to establish sources of income, they could read, they could get jobs at the hospital. It was just entirely different.

So, we continued to support that school and we found that if we could have $55 per child, per year, we could feed and educate. We could pay the teachers and we could provide one meal a day, which is the only meal most of those children get.

At the end of our 12 years of going and doing cataract surgery, we were both in our 70s and Gardner said, "It’s time for me to retire." So we told them good-bye and said we would not be back. But Pere Albert had said to us the night before we left, "I want you to come back and see a section of the mountains where there are no schools, and the Episcopal church had seven what they called "worship stations" throughout the mountains, like under a tree or a location. And he said, "My dream that I have" — and he believed that God talked to him in his dreams — "and my dream was I want a school adjacent to each of these worship stations."

Well, I said, "Pere Albert, we’re supporting one school with 400 children. And how are we going to support seven more schools?" Well, he looked at me and said, "I don’t know how we’re going to support seven schools. But there’s one thing I do know, is God wants schools in the mountains."

So, we came home with that message, and we’d been home about three weeks and I had a letter from him, and he said, "Just come and see." That was the only thing he had on it. "Your son, John Wilfred Albert." So I asked Gardner, do you want to go back even though he had retired and said he wasn’t going back. He said, no I really don’t. Would you be afraid to go alone? And I said no, I have to go. He was on his way to the golf course and while he was out I started making little lists and things about going. And he came home from his game and tossed his golf cap on the bed and he said, "I’ve changed my mind, I’m going with you." And I said, I’ve always known God talks to you on the golf course."

So we made the trip back and we went to the mountains and it was just as he said — there was one church building and these six stations and no schools. And he lived in a little house with an outdoor kitchen and an outhouse down the road. And that was it.

So we came home and of course looked at each other and said, "What are we going to do?" And Gardner said, "Why don’t you start with Presbyterian women? Presbyterian women know the importance of education. I would suggest that you write the Presbyterian women’s organizations in Louisiana and Arkansas and ask them if they would let you come and talk to them." He said, "Don’t talk for more than 18 minutes, and tell them that you will pay your own expenses to come, all they have to do is listen."

So one of my first invitations was to a Presbyterian church in Hot Springs, Ark. And I went and at that time we had slide projectors — we didn’t have DVDs — so I had my program and showed it, and I had my little basket out there and anyone who wants to contribute can. And I saw money being put in and I thought, Oh, I’m going to have a few hundred dollars. And just as I was packing my car to come home back to El Dorado, a lady came up to me and she said, "You know, we have a family foundation. I think my sister would be interested in this and she’s the president. Give me some material and let me send it to her." So I gave her what I had and I came back to El Dorado, and in about three weeks I had a check from New Orleans, where her sister lived. And it was for $10,000.

So I looked at it and I said, "God does want schools in the mountains!" And I sent the entire $10,000. Pere Albert was a man who you knew could do that. And he began building schools.

Q: Was it important having a local contact like Pere Albert?

A: They trusted him and I trusted him. And they began to weave cornstalks and palm leaves and all this together to make shelters like that.

With that $10,000 and asking for $55 scholarships for the students, we were able to build schools, hire teachers, buy books. And the culture changed. It was quiet in the mountains, no violence in the mountains. They went to church and thanked God on Sunday for what they had been given during the week.

Six years ago we established a 501(c)(3) for the Haiti Education Foundation. And we now are supporting 40 schools in the mountains, with 13,000 children.

And that’s what we do now, is speak to churches and individuals. I’ve got this down to only 16 cents a day. And we’re able to do that because we all work as volunteers and we pay our own travel expense. So if the person gives $55, $55 goes to Haiti. And that’s been the secret, really, of our success.

And so each month from El Dorado we wire the budget to a bank in Port au Prince. And I spoke of Pere Albert being a person you can trust, he developed pancreatic cancer a few years ago. He established a board of Christian young men plus two priests in the mountains who are connected to the Episcopal Church of Haiti. And when we send the wire, a copy of what we’re sending goes to each — we now have e-mail — to let each one know exactly what’s being sent and what requests have been made for it to be used. So, it’s working. This is the thing that’s exciting.

We support more Episcopal schools and the reason it is Episcopal is because the PCUSA Church — the Presbyterian Church of the USA — they chose to work in partnership with the Episcopal Church of Haiti. They did not want to go down and make "Presbyterians" out of the Haitian people. The Episcopal church was established, had a plan. So all of their work in hospitals, schools and now a new nursing school that’s gone up, it’s being built by the Presbyterian Church USA but in partnership with the Episcopal church.

Q: Do you have any stories about any of the kids you’ve met over the years?A: When we first went to Mercery, that was the first school to be established. That was where the voodoo priest was in charge. After we established the school, Pere Albert opened a little church — there was a church building there that had been boarded up for many years. And he opened it up and began to have services, and that was where our church in El Dorado opened the first school.

And so when we went back, the voodoo priest had his temple right next door to what we were using as a church — our church — so we stopped to visit with him and he said to Pere Albert, "You know, I’m going to have to leave the village now because I don’t have a following. They’re going to church. And he said, my wife has been going to church, and she wants to stay so the two children will be able to attend school." And he said, "Would you let my little boy Andre enroll in your school?" And Pere Albert said, "We would love to have him."

My daughter-in-law was with me at the time and we ran over to take a picture of Andre because we thought, to have the witch doctor’s son in school was really something. And then he said, "My wife has been coming to your church, and she wants to stay in the village for the children to go to school. And I am going to have to go out and go somewhere that you have not been so that I can establish another voodooo temple." And he did just that.

I have noticed, Haitian men, they support their children. If there’s a divorce or if they’re separated, they support their children. He would financially see that his children had what they needed and his wife had what she needed

Q: Did you ever envision creating what you have?A: It never occurred, in fact it was a surprise to even go there. We only were going to go once. We were going to go down and Gardner and Jim were going to do the surgery on as many people as they could, and we were going to go home and we’ve done that, and that’s in the past. But wen we started to pack up — we had to take our surgical instruments — and when we started to pack up to come home, there were people who had people had led them in for days. There were people out on the grounds who had not even been seen by a doctor. So that was our first trip in 1977, Thanksgiving week. And so Gardner, as we were packing up, he said, well, it’s tell them we’ll come back the week after Easter and finish. Well, we went back the week after Easter and worked another 10 days and of course we didn’t finish. So for 12 years, we went each Thanksgiving week and each week after Easter

Q: Do you have an idea of how many cataract surgeries you did?

A: Well, we did about 30 a day.

Q: So, you could easily do 300 during the time that you’re there?

A: Uh-huh.

And this was really exciting for them, because when we started that was before lens implants; we had glasses. We kept them overnight ad then took the bandage off and put what we called cataract glasses, these thick glasses on them,

Of course, they were blind when they came in, and their families would be so excited because they just wanted to stand around, there were grandchildren they hadn’t seen and it was a very emotional time for all of us, and I would take my Kleenex with me, you know, and dry my eyes.

One morning we had a very large Haitian man and he had been so excited that he was going to see. And we would hear him say in the hospital, to other people in the bed, "Tomorrow I’m gonna see! Tomorrow I’m gonna see!" Well, Gardener reached down and took the bandage off of his eye and slipped the glasses on him, and he looked up at Gardener and said, "You’re white!" Gardner said, "I just happen to be."

Q: Do you have any advice for someone who wants to help out overseas, but doesn’t know where to start?

A: I would say, anyone who’s interested in being a volunteer in mission would go to their church mission committee. Now the Presbyterian Church has what we call a Medical Benevolence Foundation. And they are in charge of all the medical missions of the Presbyterian Church USA. That is the way we started with this, is with a speaker from the Medical Benevolence Foundation. And if I had not heard a speaker and was interested, I would contact the source that is in charge of medical missions in my church. Because they are the ones who do book and plan the medical missions — people who want to go to hospitals.

When we were at the hospital there was young man there who had been accepted at Vanderbilt in the medical school, but he had to wait one year before they were going to take him in. Well, he came down and volunteered to work in the hospital He wasn’t a doctor, but there’s so many things he can do. And now he’s an intern in Denver and keeps in touch and supports the Haiti Education Foundation.

So, there are many avenues for volunteer work.

When I made my first trip I was 60. And so that’s 31 years ago so I’m 91 now.

Q: When are you planning on going back to Haiti?A: Well, I’m going back. Gardner died in ’06 and memorials were given for him, and they’re building a school, the Gardner School. And Susan (Tuberville, another volunteer with the Haiti Education Foundation) and I are going to Haiti in the next few months. I want to see the school and, you know, I just want to continue to go back.

This is the way we support the schools is to go to organizations and churches or wherever they are interested — Rotary Club in El Dorado invited us to go speak — and we explained to them that we can educate and feed these children for $55 a year, and that’s an annual scholarship. And that’s the way the schools are supported.