Working for a living: Pathology

This summer, our In Schools page focuses on career options available to recent graduates and features stories from professionals with unique jobs.

Pathologist

- Overview: A pathologist deals with the causes and nature of disease and contributes to diagnosis, prognosis and treatment. This specialist uses information gathered from the microscopic examination of tissue specimens, cells and body fluids, and from clinical laboratory tests on body fluids.

- Education requirements: The common path to practicing as a physician requires eight years of education beyond high school and three to eight additional years of internship and residency.

- Outlook: Employment of physicians and surgeons is expected to grow faster than the average for all occupations. Job opportunities should be very good, especially in rural and low-income areas where there is a perceived shortage of medical practitioners.

- Median yearly compensation for physicians: Depends on specialty, but between $137,119 and $259,948

Bureau of Labor Statistics/American Board of Medical Specialties

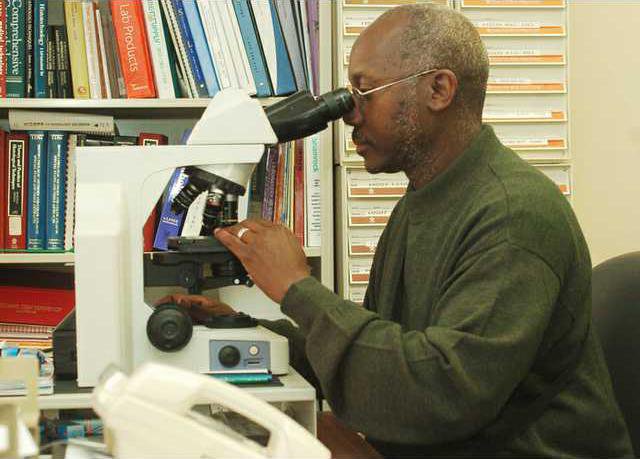

He's a clinical and anatomic pathologist at Northeast Georgia Medical Center in Gainesville and one of six pathologists at the hospital who can usually be found hunched over microscopes and tissue samples in one of the laboratories there.

Thomas is a graduate of the medical school at Columbia University and said he recommends pathology to students with an interest in the biological sciences.

"If you like science and you like a challenge, it's definitely there," he said. "You can make a difference in people's lives."

We asked Thomas for some insight into his profession, and here's what he had to tell us.

Question: What exactly does a pathologist do?

Answer: They study disease. If you're a medical pathologist, you study medical disease. If you're a veterinarian, you look at animal diseases and if you're a plant pathologist, you study plant diseases. Usually there are two areas of medical pathology - there's one area called anatomic in which you look at tissue or cells of people; the second area is clinical where you look at blood tests or test any type of fluid. The anatomic part, if a woman has a breast lump, at some point they want to look at the tissue itself. So they'll do a needle biopsy or they'll take the breast tissue out. When they take the tissue out, it will come to a pathologist. And they'll examine that tissue and give a diagnosis whether it's cancer or not cancer.

Q: Why did you decide to become a pathologist?

A: I really like science. And I think out of all the areas of medicine, it's probably the closest to science. You're looking at cells, so you're really close to the biology more so than the other parts of medicine, which are not as closely tied to the basic sciences. So if you're a person who likes more of evidentially-based things and hands-on and being close to the science aspect of it, then pathology has that aspect to it. And I like working alone. You're mostly contacting other doctors and not really talking much with patients.

Q: How much school is required to become a pathologist?

A: Four years of undergraduate school are required to meet the pre-med requirements. Then you go to medical school for four years. And then at that point you do a pathology residency. And that can vary. If you want to do both clinical and anatomic, that's a four-year residency. And then if you want to specialize, you can do additional training, which is another one to two years on top of that. I did neural paths, which is study of the brain, so that's an extra two years.

Q: Does the day-to-day life of being a doctor match your vision of what it would be like?

A: Pathology is different; it's not like what most would think of clinical medicine. We're basically going in to do research. It's more routine in pathology, because you're dealing with a variety of different tumors and prognoses occurring in different patients. But it's close to the basic science, and you're still looking at cells and you're still looking at things you can measure quantitatively. And that's the difference - you can look at things under the microscope and measure, and that's pretty much what I expected. It's exciting because you see a lot of different things. When you hear somebody has cancer, you never see it. When you hear somebody has a heart attack, you never see it. Here you actually see these things actually have an appearance.

Q: What's the best part of your job? The most difficult?

A: I think the best part is when you make a difference in a patient's life, like with any area of medicine. When somebody has something that's bothering them and you can give a diagnosis that alters the treatment and the outcome, like when somebody has a lump they thought was cancer that doesn't turn out to be cancer.

It's difficult when you have to deal with someone who does have a bad diagnosis. Even though we don't see the patient directly, you still know they're people and you have empathy there. When you see someone who has a diagnosis that has a very low chance of being cured, those situations aren't really pleasant to deal with.