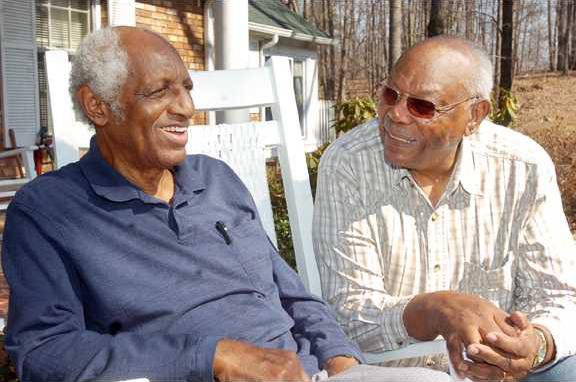

The founders of the Men's Progressive Club proved that there was more than one way to get what you want, even in the segregated South.

"When we came back from the war (World War II), we were promised many things about (equality), but we who lived in the South discovered that those promises weren't kept," said Charles Morrow, one of the club's two surviving founders. "People in other countries talked about America being the land of plenty, and it was for other races, but not for us.

"I never understood how I could go fight for a country, yet that country won't permit me to function at a level that I know I can.

"We decided that if we couldn't convince (those in power) to give us what we were promised, then we would do it on our own."

And "do it" they did. In 1950, 16 leaders of the black community decided to create an organization that would be dedicated to making sure that their community thrived.

Some of the founders of the club included Dr. E.E. Butler, Charles Morrow, Austin C. Brown, Maynard Brown, Rufus Tucker, Edgar Billingsley and Doyce Hughey.

"There were a lot of things that we wanted to see done - a lot of our ideas worked," Morrow said.

"We just had to take it step by step."

One such idea was helping blacks get a fair opportunity to vote.

"During those days, we were not permitted to vote in the local elections. Blacks were being charged a poll tax to vote, but we knew there were a number of whites who were voting without paying the tax," Morrow said.

After helping secure a federal investigation into local voting practices, the club was able to get the poll tax eliminated and thus help blacks become more active in the political system.

"Voting and politics control a lot of things. They control jobs. They control economics," Morrow said.

"Voting was a big thing, and we went for it."

Once their community was able to be a part of the political machine, the club set about making sure that the machine had parts that were supportive of blacks.

"We looked at whoever was running for whatever office and we tried to pick out the best one that was able to help the black community. We would try to encourage people to vote for that person," said W.H. Maxey, progressive club surviving founder.

"It worked real well back in those days. I don't think it would work today at all, it was a different time then."

Although the club's founders were mostly local businessmen, they also kept an eye on public safety.

"On (E.E. Butler Parkway) what used to be Athens Street, from about College Avenue to Summit Street were just about all black businesses," Maxey said.

"One night, we found out that the Ku Klux Klan was gonna ride through there. We all got together and asked the businesses to close up early.

"We tried to get the people off the street so there wouldn't be any problems."

The group also came together to make sure that out-of-town teachers had a place to live during the school year.

"There were around 60 to 75 black teachers in the schools, but they couldn't stay in the white community," Maxey said.

"A lot of the teachers stayed in private homes, but there were still some teachers who needed a place to live. A bunch of us men got together and built a home for them. It had individuals bedrooms, bathrooms for them to share and a big kitchen.

"Even if we didn't have hotels and motels we made it work. We took care of our people."

Other founders of the club were Ross Harrison, J. Wesley Merritt, T.J. Greenlee, Talmadge Yarbrough, Willie T. Robinson, Doc S. Lowe and Walter W. Chamblee.

Although the club thrived through integration, activity began to slow down as the founders died one by one, until there were fewer than a handful remaining.

"The club died out when there was only about three or four of us left. We quit having meetings," Maxey said.

After prodding from current Gainesville City Councilwoman and Gainesville native Myrtle Figueras, the remaining founders invited new members and decided to reorganize about 10 years ago.

Club members still get together for weekly meetings to discuss current affairs and local happenings, but their focus has gotten broader.

Nowadays, they're more likely to buy school supplies for underprivileged children, help a homeless family or support causes that aid American troops.

Although there have been many positive changes over the last few decades, everything hasn't been for the better. Historical buildings like the Roxy Theater have been razed and the black community isn't as close-knit as it used to be, the club's founders say.

"On (the old) Athens Street, there were five or six restaurants, barber shops, beauty parlors, a movie theater, funeral homes and veterans clubs ," Maxey said.

"Now we don't even have one sit-down restaurant. Now, there are plenty of places to go, but they're not in this community."