In the late 1960s, Eliot Wigginton was a still green teacher, taking on his first post-college job at Rabun Gap Nacoochee School in rural North Georgia.

He was presented with a classroom full of restless students, who were largely unsinterested with his English lessons — one even set fire to his desk to keep from working.

"My dad honored the law requiring you to go to school, but he thought your diploma ought to be calloused hands (from hard work)," said Barbara Taylor Woodall, a 1973 graduate of the Rabun Gap school. "I always said that my brothers had one foot in the classroom and the other on unbroken sod for looking at the south end of a mule. Corn was life ya know, so we didn’t put a lot of stock in (formal) education."

It was, and still is, produced mostly by Rabun County students.

Woodall refers to Wigginton’s idea to create a magazine telling the stories of life in the Appalachian Mountains and sharing their traditions and customs as a "miracle in education."

"That miracle touched my life about six years after its original founding. I had a straying teenage mind and had plans to quit school when I turned 16 and get a job like some of the mountain people did," Woodall recalls.

"The passing of my beloved Granny Lou keened my interest in what this young school teacher was talking about when he arose from a student desk where he sat among us and pointed out to the mountain ranges framed by the big windows of the Nacoochee (school) building and said, ‘Our classroom isn’t in here, it’s out there.’

"He said, ‘Your grandparents are dying off and taking a way of life with them that will be lost forever, unless we do our part to record it.’ After that, it was instilled in me and other students the importance of our heritage.

"That ignited a very needful and addicting flame inside me and the other students to prowl these mountains with tape recorders. Many students became the lantern inside the Foxfire. Crawling through whatever we had to, to show our heritage to the world."

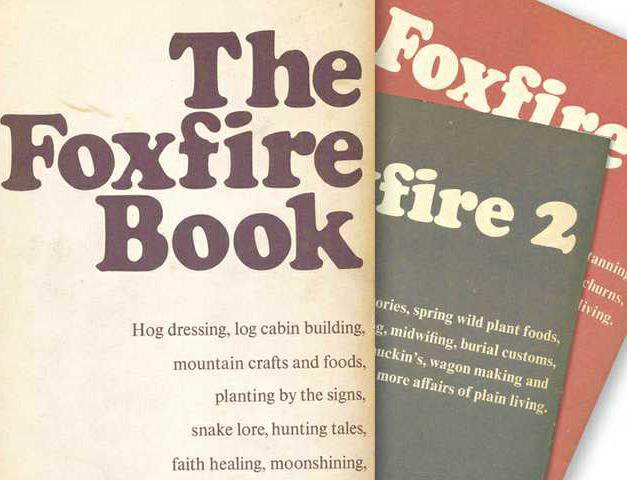

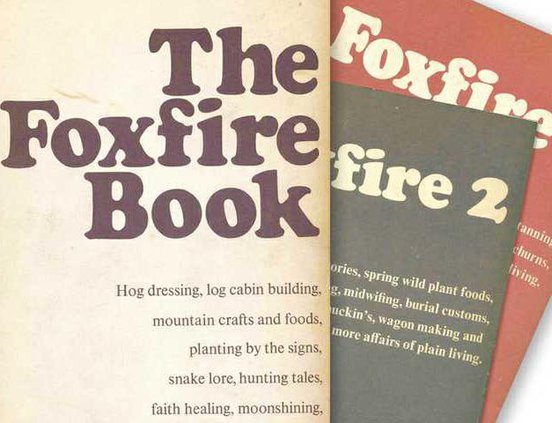

Shortly after its creation, the magazine’s popularity spread like wildfire. The publication’s articles went on to become compiled into a 12-volume Foxfire Book series.

The books’ how-to articles on topics like building a log cabin, weaving baskets and medicinal uses for herbs helped to preserve skills that were being lost as elders passed away.

"The books have sold something like 9 million copies," Woodall said.

"It succeeded because our hearts and our souls were knitted together in a joint purpose and that was the preservation of a dying lifestyle."

The common sense knowledge shared in those books is not only relevant today, it’s also necessary for preserving Appalachian culture and traditions, Woodall says.

"The values I was taught by our many elders, my family and Foxfire contacts were precious. They taught me the things that really matter like faith and hope and love and appreciation," Woodall said.

"Them kind of things are worth passing on to the younger generation. I know they can never go back and live the lifestyle that I did, but they can learn from it and hang on to the values."

In the Foxfire tradition of telling stories and sharing knowledge, Woodall has recently completed a book — "It’s Not My Mountain Anymore."

"My book chronicles the many changes I’ve seen in the mountains over the last 50 years, both good and bad. I think one reason it’s popular, especially regionally, is because people are hungry for mountain stuff," Woodall said.

"It don’t have no $5 words in it cause I don’t know none. It’s just plain talk. It’s pure mountain stuff. This is a pure dose of Appalachian reality. That’s my grandson (on the cover) drinking out of the creek right beside my house.

"He’s 10 years old. We’re teaching him the ways of the mountains as much as we can and as much as he can absorb. He has a healthy respect for nature. He knows to preserve it."

‘We ain’t immune no more’

Woodall also uses her book to recount many of her Foxfire experiences, including an interview with a then 77-year Maude Shope, who was still riding her mule in the 1970s for transportation and utility. Shope predicted the changes on the mountain that Woodall has seen come to fruition. "There is many more people being born that have to have a place to live. We’ve got land here. In a few years, they’ll cut it up and they’ll take off so much and sell it,’" Woodall writes in her book from the interview with Shope. "That worries me." Although Shope died before a then teenage Woodall could publish her article, her words rang true to the Rabun County native. "We don’t know our neighbor anymore. My greatest concern as a child in these mountains was getting bee stung or snakebit. (My grandson’s) greatest concern is getting run over or God forbid enticed by drugs," Woodall said. "These mountains used to protect us from a lot of outside stuff, but we ain’t immune no more. Several years ago, just across the creek from where I live, they busted the biggest meth lab in North Georgia. And I didn’t have a clue what was going on. "No doubt they poured their (waste) in the creek and it washed down to a nice community park where dogs drink and kids play. Right there under my nose I didn’t know it. You didn’t hear about that in my day."

A noble heritage

As a child, Woodall recalls being proud of her birthright, but the negative portrayal of mountain natives in movies and popular culture caused later generations to be ashamed. Woodall hopes a renewed interest in the Foxfire publications, her book and the Foxfire Museum and Heritage Center in Mountain City help to clear up misconceptions in the general public about mountain culture. She’d also like to see them be used as tools for helping future generations be proud of their roots again. "I long for a time when you left your keys in the car in case your neighbor needed it. Them was the days, but you can’t go back," Woodall said. "It’s not realistic to freeze an area. You can’t. We have to buck up and cope with change, just like our pioneers did. I hope my grandson (and future generations) learn to appreciate their birthright, but I don’t want it to be a burden. "We have a noble heritage. I’d like people to get to know the natives up here — we’re not weird or perverted. "I’d like people to be kinder to our ways and traditions. There is good people here."